Consultants, stakeholders, algorithms, scores and activity-based funding have replaced plain old-fashioned caring.

I love change: the earthy ceremony of turning a sod fills me with joy.

The ground-breaking always goes with optimism. It’s like opening a door to a better way, or cutting a ribbon, allowing us to cross into Utopia. Though sometimes I must ask: Is the new way better or simply more complicated?

I want to reflect on our treatment of the elderly in healthcare and how our best efforts to assist in a dignified death have evolved. Allow me to set the scene.

In the “bad (substitute good as you wish) old days”, hospitals were run by a holy triumvirate: a medical superintendent, who still treated patients; a director of nursing – a Mother Superior type who could summon delicious tea and scones; and a bookkeeper who generally ran in the red. The first two provided pastoral care to their flock. There was block funding and little real accountability. Above all, there was always a surfeit of beds. Consequently, there were no bed managers.

The capital works were often financed by local chook raffles and bequests. General practitioners did their own on-call 24/7 and had hospital admitting rights for their patients. Somewhere, usually by a side street, you could access the Casualty. These were generally quiet places, known best by the ambulance service, the police, the Salvation Army folk, and a few frequent flyers after a bed for the night.

This was a time when the elderly were happy to die at home in dignity, reverently surrounded by loved ones. General practitioners facilitated this model of care by regular home visits and appropriate palliative sedation. On rare occasions there was no one to provide filial care. The frail and neglected, living alone, usually widowed ladies, without a regular GP, would fall through the cracks.

Ambulances would deliver these vulnerable folk to the casualty. They were usually displaced in some border town between life and death. As junior doctors we would make up dark humour diagnoses such as “acopia” or just write “social admission”. The hospital social workers would affectionately assess them for comfort and appropriate placement. There was minimal medical interference. Advance care directives did not officially exist, but the concept was acknowledged and respected.

The exception was when some remote child would appear from interstate and don the cloak of an alpha son or daughter to assuage years of their own neglect, by demanding heroic “cutting edge” measures, ignoring the truth that these would be both futile and rob any last vestige of human dignity from their loved one. This was to establish dominance in the changing of the family guard, and for no other purpose. That’s a tale for another time.

Over the years health became politically weaponised and industrialised, attracting more and more stakeholders. Quality improvement models were appropriated from automobile manufactures like Toyota. There was a mad rush towards decreasing variance using a McDonald’s model: all hamburgers (medical care) had to be the same. I have never had a gourmet anything from Maccas.

The apparatus for achieving this nirvana was endless accreditation, producing another stakeholder. Clinical governance sprouted to mitigate risk (substitute butt-covering as you wish).

Fiscal governance began to be driven by activity-based funding, with predictable pushback by way of refined gaming manoeuvres. Importantly, due to the activities not appearing in the International Classification of Disease coding inventories, “acopia” and “social admission” were not billable. Compassion was not a Key Performance Indicator.

Paradoxically, heroic but futile measures are billable. “Unnecessary” interventions are often rationalised as a way of providing skills training and maintenance for technical measures required by others, on those who have not yet reached genuinely frail status. Put bluntly, they are practice meat.

At the same time nursing homes were corporatised. There was a mass expansion while nurse numbers were reduced to near extinction, calling into question why the use of the word “nursing” was in the masthead. The aged care facility market boomed, with “care” being ambiguous. At the same time the humble Casualty became a health supermarket with new branding: EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT.

Frail elderly folk have lots of co-morbidities and could now become an attractive money spinner. Overservicing showed fiscal smarts. All that was required was for the intern to use the correct words so that the coders could mine the seams of gold. Now back to the future.

At a recent hospital Grand Round, I heard about Residential Aged Care Facility Support Services (RaSS). This is a new medical service model redesign, championed by both the Commonwealth and state health departments. Oversight in Queensland is provided by Clinical Excellence Queensland.

The RaSS model aims to provide collaborative care between RACF and GPs. The desired outcome is increased patient choice of care setting and improved quality and safety. If a patient becomes unwell, the GP or nursing staff at the RACF can contact the RaSS for advice and support. The resident’s acute care needs are assessed, and the most appropriate care delivery service is matched to these needs. A by-product is ED avoidance.

If necessary, the RaSS can arrange for a specialist nurse or ED doctor to visit the RACF to provide ED substitutive care. This means the patient can receive care in familiar surrounds under a framework of patient quality care and safety. If transfer to hospital is required, the RaSS can ensure that the receiving emergency department receives high-quality clinical handover prompting activation of appropriate services for the arriving patient.

The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Screening tools are extensive, but the centrepiece is the Clinical Frailty Scale. Frailty has been declared a medical condition defined as “a state of increased vulnerability, associated with but distinct from increasing age and multi-morbidity, resulting in disproportionate adverse health outcomes following a stressor”.

A Clinical Frailty Scale score of greater than 7 equates to the clinical goal of assuring comfort and maintenance of human dignity. Exactly what our social workers did five decades ago.

What we oldies did using gestalt has been translated into a joint state-Commonwealth bulk funded innovation. The ED superstore now does home delivery and take out.

I still maintain that we here in Australia have one of the best health systems in the world. We have voluntary assisted dying. We have fantastic palliative care services. Fourteen percent of the Australian population currently have an advance care directive in place.

Still, we have replaced the simplicity of a casualty junior doctor and a social worker sometimes working in partnership with an old-school GP relying on normal native intelligence, with an ED consultant and a bevy of clinical nurse consultants using complicated algorithms.

That frailty has been declared a medical condition represents a landmark turning of the sod. But at what expense, and who or what, really is the sod? Five decades ago it was so simple, and I would love to hear from health economists about the value proposition (substitute return on investment as you wish).

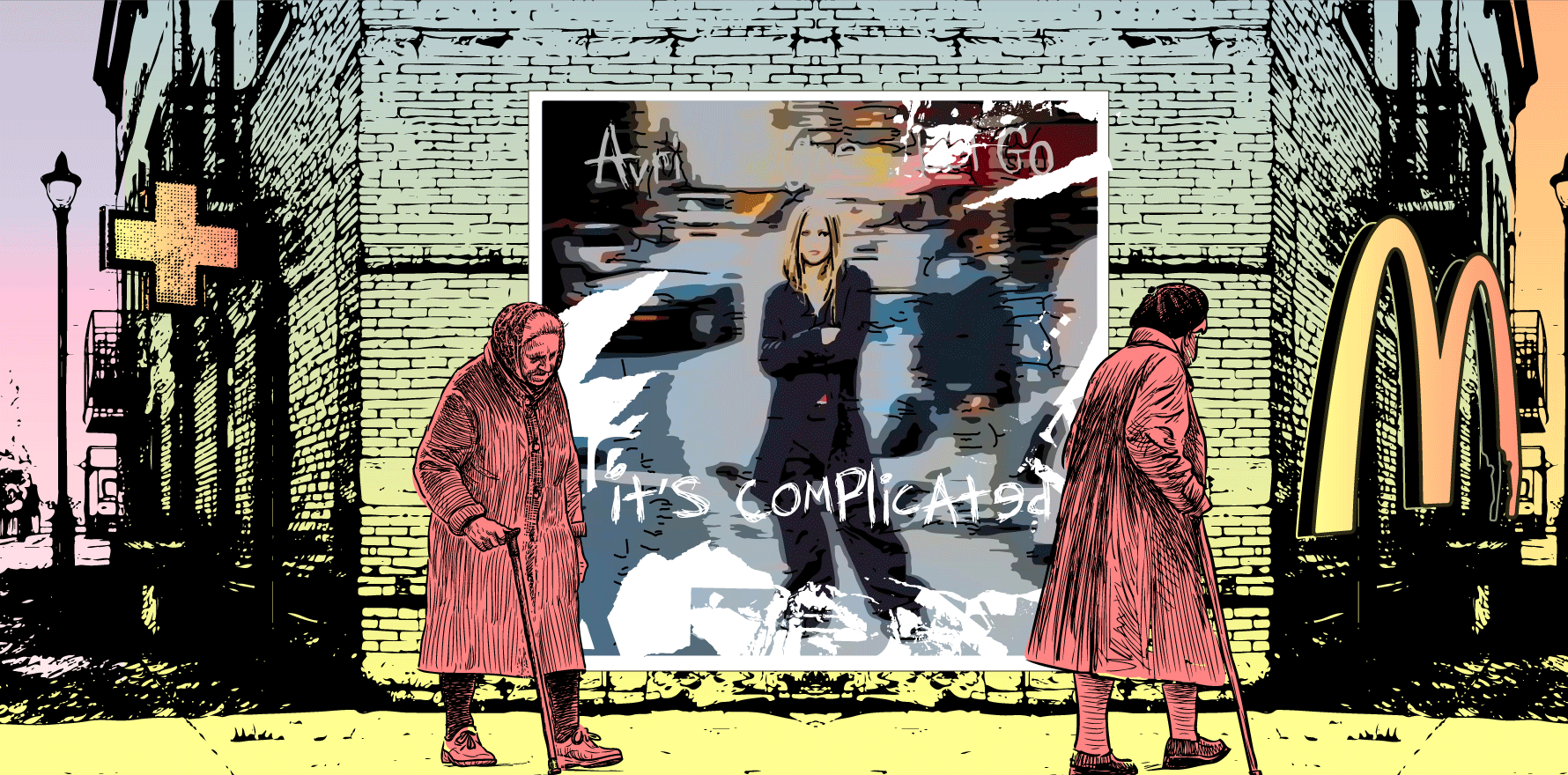

But possibly mine is a false memory. Maybe it is time to tune out and listen to the classic Avril Lavigne song Why’d you have to go and make things so complicated?