Diagnosis of subtle avulsion fractures is fraught with difficulty on MRI, since bony fragments are difficult to visualise on MRI.

HISTORY

A 14-year-old boy presented with pain and inability to weight bear following a rugby injury a few days prior to presentation. On examination, the knee was locked in flexion, and there was significant swelling and a palpable effusion. There was a positive Lachman’s test for anterior cruciate ligament injury, and a clinical suspicion for a meniscal tear.

At MRI, the patient could not be scanned in the usual position of relative knee extension lying supine and was thus scanned with the knee flexed (due to locking of the knee), in lateral decubitus.

IMAGE FINDINGS

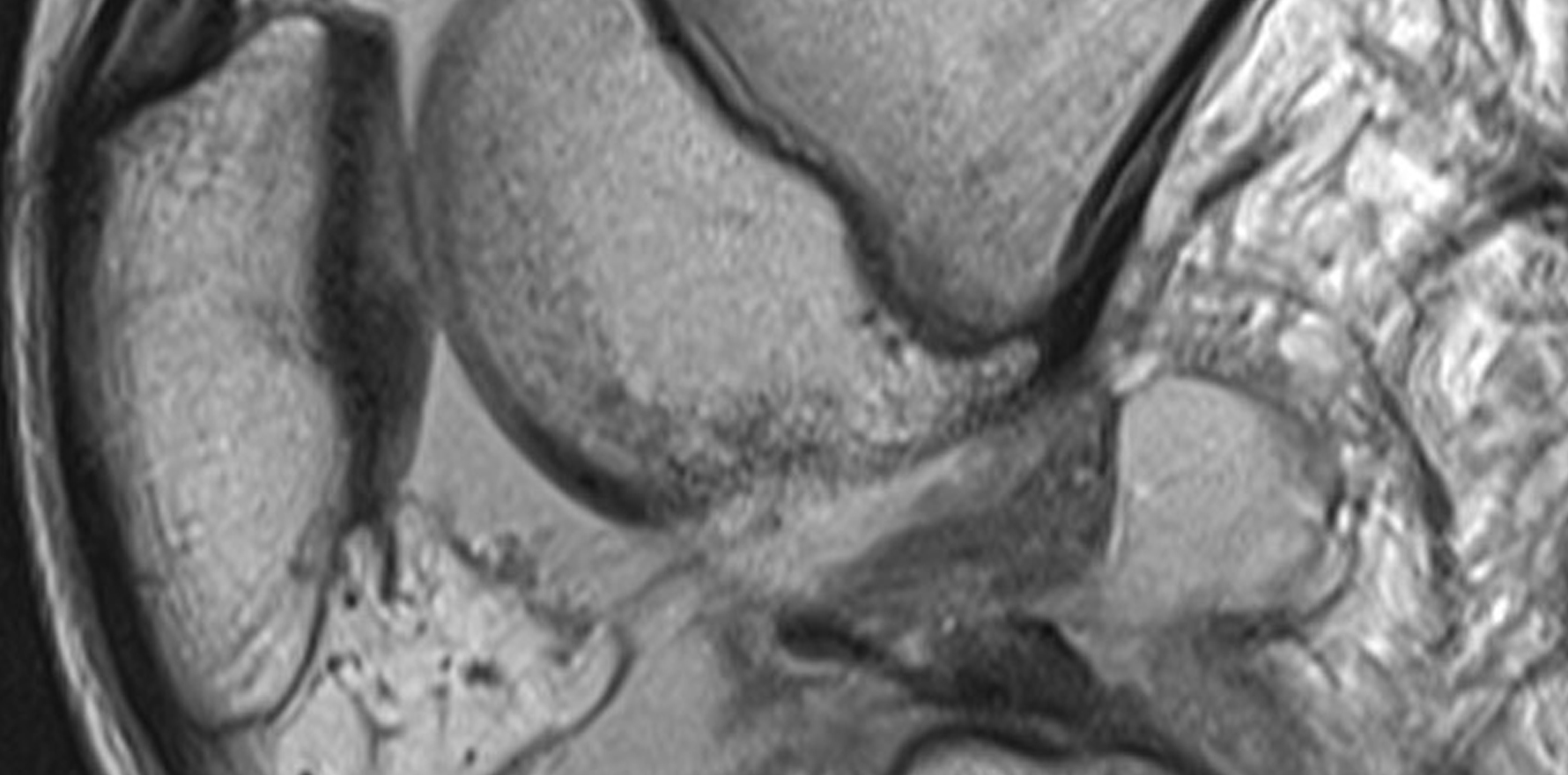

The sagittal fat saturated images demonstrate a lateral meniscal bucket handle tear. This is characterised by the abnormal position of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus which has flipped anterior to abut the anterior horn, such that there appears to be “two anterior horns” (Figure A).

In addition, there are signs of loss of ACL functional integrity. The typical bone contusion pattern in the lateral femoral condyle (at the sulcus terminalis) and at the posterior margin of the lateral tibial plateau is almost pathognomonic for ACL disruption. This is labelled a “pivot shift injury”. (Figure A)

Indeed, on sagittal images through the ACL, the ligament appears wavy and high signal, indicating a torn ligament. However, on close inspection of the ACL on sagittal PD images, there is a linear low signal structure at its distal end. (Figure B)

DIAGNOSIS

In imaging, completely straight lines rarely occur naturally in the body and often herald either pathology or medical intervention (surgery, radiotherapy, et cetera). In this situation, this appearance is suspicious for an avulsion fracture of the ACL tibial footprint and is important to distinguish this entity from a simple ACL disruption as management is entirely different (fracture fixation versus ACL reconstruction).

However, diagnosis of subtle avulsion fractures is fraught with difficulty on MRI, since bony fragments are difficult to visualise on MRI (bone appears hypointense/black, much like ligaments, tendons) and typically, avulsion fractures exhibit little marrow oedema especially as compared to impaction fractures.

Corroborating evidence comes in the form of a lipohemarthrosis. This is when there is the presence of fat and blood in the joint, which can really only be due to fatty marrow leaking into the joint due to an intra-articular fracture.

This is characterised by a “fat-fluid level”, i.e. a straight line delineating fat which is less dense and floats to the non-dependent surface from fluid which is more dense and sinks to the bottom. This situation is much like when oil floats to the surface in soup.

On MRI, this appears as fat signal in the joint floating superficial to the denser blood which sinks to the bottom.

However, in this case, since the knee was scanned with the patient on the side, this fat-fluid levels looks like it is on the side of the joint. (Figure C,D). It makes sense however as soon as you view the images in the orientation the joint was scanned – i.e. sideways! (Figure F)

ANALYSIS

This case illustrates the difficulty in delineating avulsion fractures on MRI, due to the subtle nature of bone fragments on MRI, as well as the paucity of marrow oedema.

In this situation, the presence of a lipohemarthrosis helped to make a diagnosis of an ACL footprint avulsion fracture certain.

It is interesting on a number of levels, in terms of the fact that it was scanned in flexion, with the patient lying on the side, causing the fat fluid level to be located on one side of the joint rather than in its usual location anteriorly.

Dr Sebastian Fung is a musculoskeletal radiologist who undertook an MRI imaging fellowship in Hospital for Special Surgery in New York. He now works in Sydney at St Vincent’s Private Hospital and Mater Hospital