Rheumatologists, like other specialties, are divided over the use of this drug

There is still limited evidence to support the use of medical cannabis for rheumatic disease, but the reality is many patients are trying cannabis already, US experts say.

Presenting the “pro” case for medical cannabis, Dr Alvin Wells, a rheumatologist from Wisconsin and medical director of a medical cannabis evaluation clinic, said preclinical data and consumer surveys provided some support for the use of medical cannabis for osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis.

“The preclinical trials suggest that something might be there, but we need to have more data,” he said.

While there are no formal RCTs for the use of cannabis for pain relief in patients with fibromyalgia, the US National Pain Report 2014 survey of 1,300 fibromyalgia patients found that around 60% who had tried medical cannabis found it “very effective”, whereas only about 10% of patients using FDA-approved medications (such as duloxetine, milnacipran and pregabalin) found those drugs very effective for pain relief.

The cannabinoids dronabinol (THC) and nabilone have both been tested in small clinical trials in patients with fibromyalgia. These studies reported that patients taking these cannabinoids had reduced pain levels within two hours, as well as improvements in sleep and mood.

This is despite a 2016 Cochrane review of the evidence that found that “nabilone did not convincingly relieve fibromyalgia symptoms (pain, sleep, fatigue) better than placebo or amitriptyline”.

In terms of rheumatoid arthritis, preclinical research had proposed a mechanism through which cannabinoids might relieve joint inflammation in patients via CB1 and CB2 receptors, Dr Wells said.

And Cochrane reported in 2012 that there was weak evidence that oromucosal cannabis was superior to a placebo for rheumatoid arthritis. However they also said the potential harms (including dizziness, dry mouth, light headedness) from cannabis “seem to outweigh any modest benefit achieved”.

But as Dr Wells pointed out, the harms associated with medical cannabis needed to be weighed against the risk of addiction and overdose from alternative pain medications.

“In the US there has been an increase in death from pain medications,” he said.

“However, in states where medical marijuana has been approved, total opium prescriptions and deaths from overdose have gone down.”

Medical cannabis had been legalised in more than half of all US states now, so rheumatologists can’t “stick their heads in the sand” and fail to engage with the issue, he said.

“Whether you are for or against it, I think medical marijuana is here to stay,” Dr Wells said.

Presenting the “con” case against medical cannabis, Dr Duane Pearson, an associate professor of rheumatology at University of Colorado, said doctors should take a harm-minimisation approach when talking to patients about their choice to use medical cannabis.

The risks from medical cannabis were not trivial, Dr Pearson said.

An increasing number of driving accidents were related to cannabis use; around 9% of cannabis users became addicted to the substance; cannabis use was correlated with the onset of schizophrenia in some patients; vaping or smoking a cannabis joint put volatile compounds into the patient’s lungs and increase their risk of lung cancer; dirty bongs could cause recurrent lung infections; taking cannabis during pregnancy could harm the fetus; and children could stumble across brownies or cookies laced with cannabinoids with serious consequences, he said.

Rheumatologists would also have trouble prescribing cannabis because there were so many ways of inhaling or ingesting it, and it was unclear what mix of THC and CBD would have the desired effect, he said.

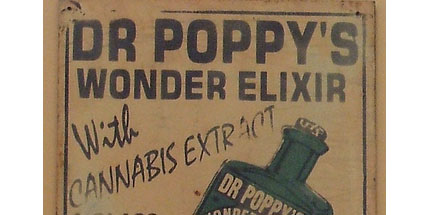

Before cannabis distribution was criminalised in the US, it was one of the most popular medical treatments around, Dr Pearson said.

Along with cocaine for toothaches and laudanum for restless infants, cannabis would often be found among the elixirs and tinctures rolling into country towns on medical show wagons in the late 1800s, he said.

Cannabis was so widely used that the American Medical Association even criticised the decision to outlaw cannabis in 1937 because of its perceived medicinal value.

Because cannabis had been an off-limit drug in the US for so many decades, there just wasn’t any convincing research for its efficacy for many indications yet, Dr Pearson said.

“So, we go back to a place of many promises: ‘cannabis reduces inflammation, it reduces blood sugar levels, promotes bone growth, relieves anxiety, it’s an anti-bacterial’,” he said.

“This is based on animal data at best. There is very little data in humans that it works as an anti-inflammatory drug – but [cannabis advocates say] ‘we will sell it to you’.”