It’s easier than ever to obtain a GLP-1 drug thanks to text-only healthcare startups.

Last week we tried a little experiment. One member of staff had a go at using a telehealth service to obtain weight loss medicine.

Despite the staff member lying about their medical history and weight, they managed to get approved for treatment with Saxenda by a doctor who had not spoken to them, seen them or confirmed their identity.

The strangest part, though, is that there is little that the regulators can do.

The players

Eucalyptus, the company that owns telehealth-only brands Pilot, Kin, Software and Juniper, was founded in 2019 by marketer and brand manager Tim Doyle.

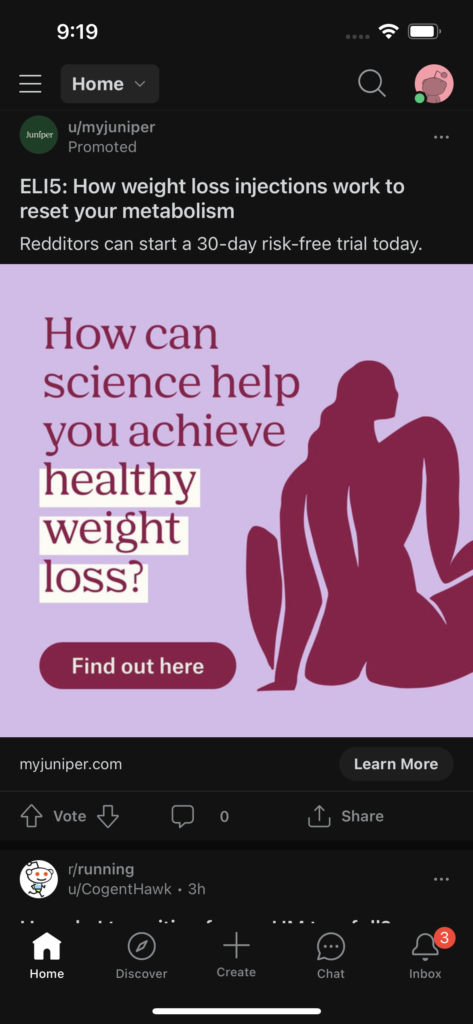

The Eucalyptus suite of brands are some of the most visible telehealth companies operating in Australia, inundating social media with trendy, colourful and youth-focused advertisements.

Its success isn’t theoretical, either – so far, it’s raised $98 million from venture capital investors through four funding rounds.

Another key telehealth player in this saga is Mosh, which was founded by two former business consultants. Mosh also counts two founders of Tinder among its advisors and has raised $6.4 million over two funding rounds.

Because these services are designed to be online-only, with no face-to-face meeting between doctor and patient, patients pay entirely out of pocket.

The medicines prescribed by telehealth company doctors are not PBS-listed for weight loss.

Of the five brands mentioned so far, three of them – Pilot, Mosh and Juniper – offer prescriptions for weight-loss medicines.

Both Pilot and Mosh are geared toward men and also offer treatments for hair loss, erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation, acne and mental health.

On the Eucalyptus site Juniper is labelled as a “women’s healthcare” brand, but the “about us” page of the Juniper website reveals a more explicit singular focus on weight management.

None of them mention the brand name of the weight-loss medicines that their doctors will prescribe up front – all three cite regulations that prohibit advertising medicines directly to consumers – but both Eucalyptus brands specify GLP-1 receptor agonists as being on offer.

Writers at Rheumatology Republic have been served ads from Juniper on social media platforms recently, inviting them to read articles on how weight loss injections work and offering a 30-day “risk-free” trial.

The patients

The journalist who decided to try their luck at getting a GLP-1 receptor prescription chose Pilot.

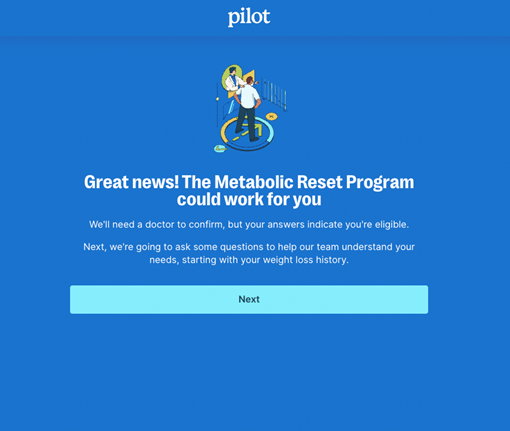

It was simple to get onto a quiz to determine eligibility for its “Metabolic Reset Program”, which promised to address their weight on a cellular level.

The standard questions included sex at birth, age, weight (our journalist exaggerated their current weight), previous medical diagnoses, allergies, current medicines and previous weight loss methods that they had trialled.

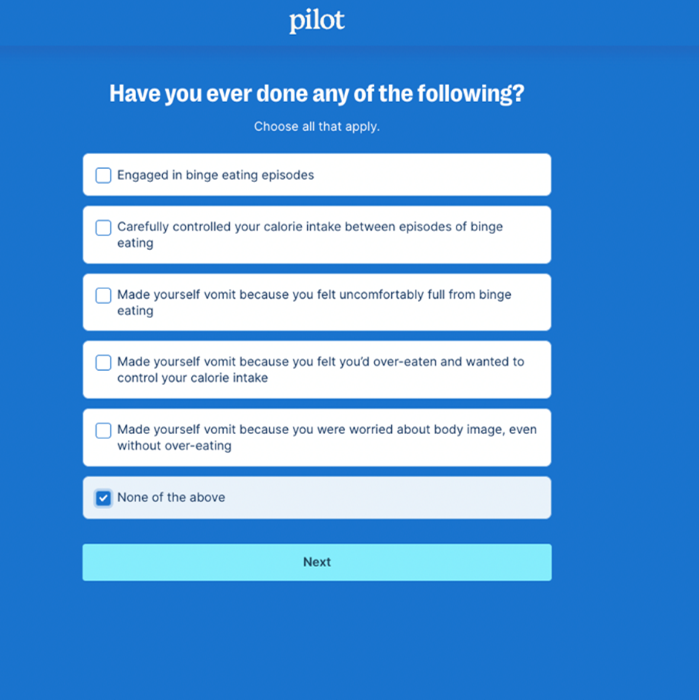

One section asked the journalist whether they had engaged in binge eating, controlled calorie intake or made themselves vomit in the past. Our journalist simply checked “no”.

And just like that, they were approved for the Metabolic Reset Program pending a doctor’s approval.

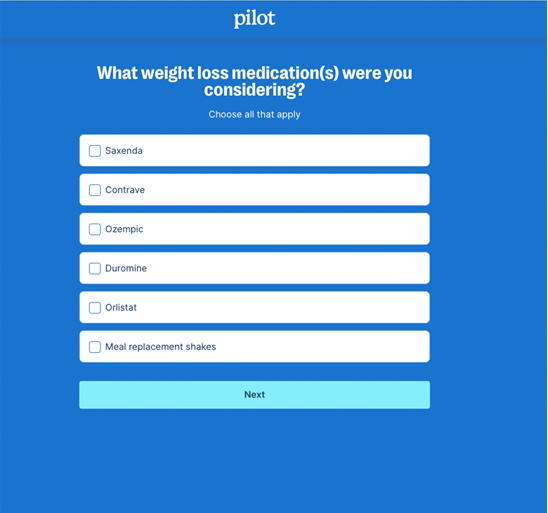

The next set of questions asked our journalist about their weight loss history, how weight impacts their mood, diet, exercise, sleep patterns and whether they had considered weight loss medicine before.

It then came to a screen with a drop-down list of brand-name medicines and asked the reporter to select the specific medicine they were considering.

After asking for details on insurance and how much they were willing to spend on weight loss per month, information popped up informing the journalist that Pilot’s most effective weight loss program stated at $13 a day, which adds up to $395 a month.

Seem steep? Pilot had a ready answer.

“Our medication works to suppress your appetite and keep you fuller for longer,” the following paragraph reads.

“As a result, many people on the program report savings on grocery bills, eating out and consuming alcohol.”

The final step was inputting more medical history, after which the journalist was again advised that a doctor will review the responses.

Pilot counted this as a consultation but waived the $20 fee as part of a promotional offer.

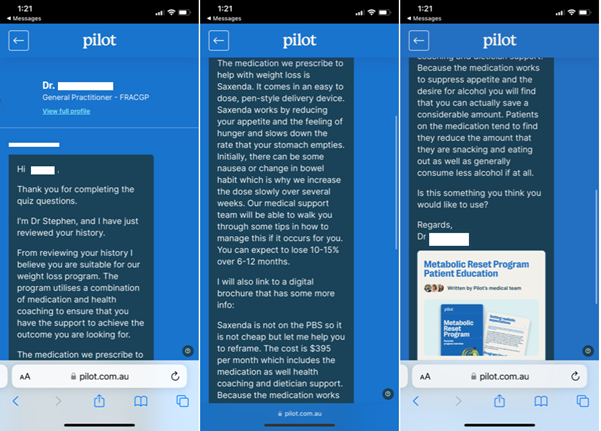

Just an hour later, the verdict was in – a GP in another state had reviewed the quiz and believed the reporter was suitable for the $13-a-day weight loss program, which included a Saxenda script.

They were advised that they could expect to lose 10 to 15% of their bodyweight over the next year.

Eucalyptus said its consult protocol was robust and designed to complement the relationship a patient has with their GP, rather than replacing it.

“Consults include a detailed assessment of patient history through an assessment form containing in excess of 80 questions, a text-based conversation with a doctor and, where prescription medication is indicated, review by a pharmacist,” a spokesman said.

“This is often far more information than would be provided in a standard GP appointment.”

Further to that, the spokesman said, around 40% of interested customers are deemed unsuitable for the Eucalyptus weight-loss programs and are advised to see their GP instead.

“For many people, being able to access to private, convenient medical advice from the security of their own home on sensitive issues to do with their weight or sexual health makes a significant difference,” they said.

Mosh did not respond to a request for comment.

The regulators

Given that the entire model is user-paid, neither the MBS nor the PBS is involved, giving telehealth operators a comparatively wide scope in terms of regulatory settings – the PSR is not going to come knocking any time soon, for example.

One of the areas that is heavily regulated, though, is the advertising of therapeutic goods, which falls under the remit of the TGA.

Whether the TGA can act will hinge on whether it considers ads like the one served to our writer as promoting a health service or as directly or indirectly promoting the use or supply of therapeutic goods.

Asked whether it was investigating Juniper, Pilot or Mosh, the TGA said it was aware of the advertising, but could not comment on ongoing investigations that could result in compliance action.

“The TGA has been responding to allegations of unlawful advertising of a group of prescription-only medicines for weight loss since early 2022,” it told us.

“From 1 July 2022 to 2 March 2023, the TGA has requested the removal of over 3500 advertisements of weight loss medications including Ozempic and Wegovy (semaglutide) Trulicity (duaglutide) and Mounjaro (tirzepatide).”

Outgoing TGA head Professor John Skerritt said that, outside of advertising, the regulator can also go after businesses when it’s clear that a Schedule 4 drug has been provided without the involvement of a registered medical practitioner.

“A few years ago, we won a $10 million court case for peptides being sold over the web with no evidence of a medical doctor involved,” he said.

“Now, unfortunately, we didn’t get the 10 million because the company went bankrupt. But it did close down.”

But because telehealth operators like Mosh and Eucalyptus do have doctors on staff – doctors who declare themselves fellows of the RACGP – it’s a much harder case to prove.

“Unfortunately, in some of these fairly poor-quality medical practice examples, there actually is a doctor involved – it might be a doctor sitting at a computer terminal who’s paid exorbitant amount an hour and you can argue about the ethics and quality of care he or she’s giving,” Professor Skerritt said.

Essentially, the fact remains that a doctor is involved, rendering this route somewhat of a moot point.

The non-regulators

Enter the medical defence organisations and colleges – organisations that don’t have regulatory teeth but do have a say over what can be considered good medical practice.

Earlier this year, Avant Mutual changed its Practitioner Indemnity Policy to exclude cover for asynchronous consults, citing concerns over the quality of services when there was no real-time interaction or access to the patient’s medical records.

“We’ve seen some of the MDOs withdrawing cover for these services, which I think speaks to the concern,” said RACGP vice president Bruce Willett.

“There is obviously a concern around this way of practising medicine.”

Dr Willett said telehealth operators like Eucalyptus and Mosh reduced the quality of the health system by undermining continuity of care.

“This is part of the same conversation about the North Queensland pharmacy trials and the question is, you know, are we talking about health care or are we talking about getting drugs?” he said.

“And this should be a conversation about health care – if it’s a conversation about getting drugs, then, you know, [may as well be] available on the supermarket shelves.

“We need to bring it to be back to being a conversation about healthcare.”

He also pointed out that the system is ripe for exploitation by patients who have eating or body dysmorphic disorders.

Certain things that would be obvious in a face-to-face or even video encounter – such as whether the person is who they say they are and the weight they say they are – are simply not verified in text-based consults.

“We know that there are a significant amount of people with body dysmorphic syndrome, up to and including anorexia nervosa, but even people without anorexia nervosa but with body dysmorphic syndrome,” Dr Willett said.

“It’s very easy for them to actually lie or put in information that’s wrong but that they truly believe, and inappropriately access these medications, which could potentially be harmful.”

There’s also an aspect of preying upon shame, especially when it comes to men.

Both Pilot and Mosh treat a range of conditions that have long been classed as shameful for men – erectile dysfunction, hair loss, acne and weight.

Copy on the Mosh website even alludes to the fact that these conditions are considered embarrassing, and that GPs will likely lack compassion.

The spokesman for Eucalyptus also appeared to insinuate that people were too embarrassed about weight loss conditions and sexual health to visit their regular doctor.

“By playing up the shame aspect and saying, ‘you may not want to see the doctor, because you might be ashamed’, is actually increasing that [shame] and is actually highlighting that this is something you might want to be ashamed about,” Dr Willett said.

AMA president Professor Steve Robson said the association supported continuous patient-centred whole person care, and that it had concerns about the direct-to-consumer advertising employed by some telehealth operators.

“It would appear that some of the advertisements imply that a consult or a monthly subscription will guarantee you access to prescribed medicines,” he said.

“These services are not genuine health businesses and we again encourage people considering one of these services to speak with their GP.”