Much of what we were taught early in the pandemic is wrong; the message about aerosols needs updating.

US President Joe Biden’s administration has begun shipping free N95 respirators to all US citizens.

This is both welcome and radical. It recognises two components that have long been missing from an evidenced-based approach to managing the highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2. First, that significant transmission occurs via aerosols, and secondly that the gold standard of masks, or respirators, provide efficient protection against such aerosols, and should replace the use of surgical and cloth masks.

These are major departures from positions held two years earlier. These moves have been driven by important debates and transparent information exchange among the US government, academic circles and the mainstream media.

At the start of the pandemic, the conventional public health view was that SARS-CoV-2 transmission was via particles >5-10µm diameter – droplets – generated during coughing, talking and other respiratory activities, and thence via virus-contaminated surfaces (fomites). Smaller particles, termed “aerosols”, <5µm, were clinically important only when generated by certain “aerosol generating” medical procedures. Thus, healthcare workers, were advised to use “droplet precautions”, including surgical masks, when managing suspected-covid patients, except during aerosol-generating procedures, when N95 respirators were to be used.

The public were widely advised to wear “a mask”, and home-made cloth masks were widely promoted, including by the US Surgeon General. The market was quickly flooded with fashionable cloth masks of dubious effectiveness. This was also done to protect the limited supplies of more-efficient commercial masks for use by health care workers.

Much has changed in two years. Observations of super-spreader events that could not be explained by droplets forced the recognition that aerosols were important in both community and nosocomial transmission. Indeed, it was also accepted that a significant portion (~10-30%) of the total volume of respiratory fluid emitted during particle-generating activities such as breathing, talking, singing, shouting, coughing and sneezing were aerosols; it was not all “droplets”. Studies of airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus showed around half or more to be associated with aerosol-sized particles.

During this time, definitions and terminology have changed. The emerging view is that particles <5µm should be termed “fine aerosols” while those >5 to ~50-150µm (opinions differ) are “coarse aerosols”. Those >50-150 µm are now “droplets” (ironically, their original 70-year-old definition). Fine and coarse aerosols are now credited with remaining airborne longer, shrinking by evaporation to much smaller particles, rather than falling rapidly onto surfaces as does a spray of droplets.

The relevance of 5µm is that particles of this small size effectively remain suspended indefinitely in airstreams, easily pass through any gaps between a poorly fitting mask and the face, and require masks to have more effective filtration systems to remove them. Small particles also penetrate more deeply into the airways and some evidence suggests they are more likely to cause severe disease.

The US decision to promote and provide N95s acknowledges that different types of masks differ greatly in the protection, and that using the most effective mask is a cost-effective public health measure. It also indicates that the past two years have been spent preparing for this, by massively increasing the supply and quality of once-scarce N95s.

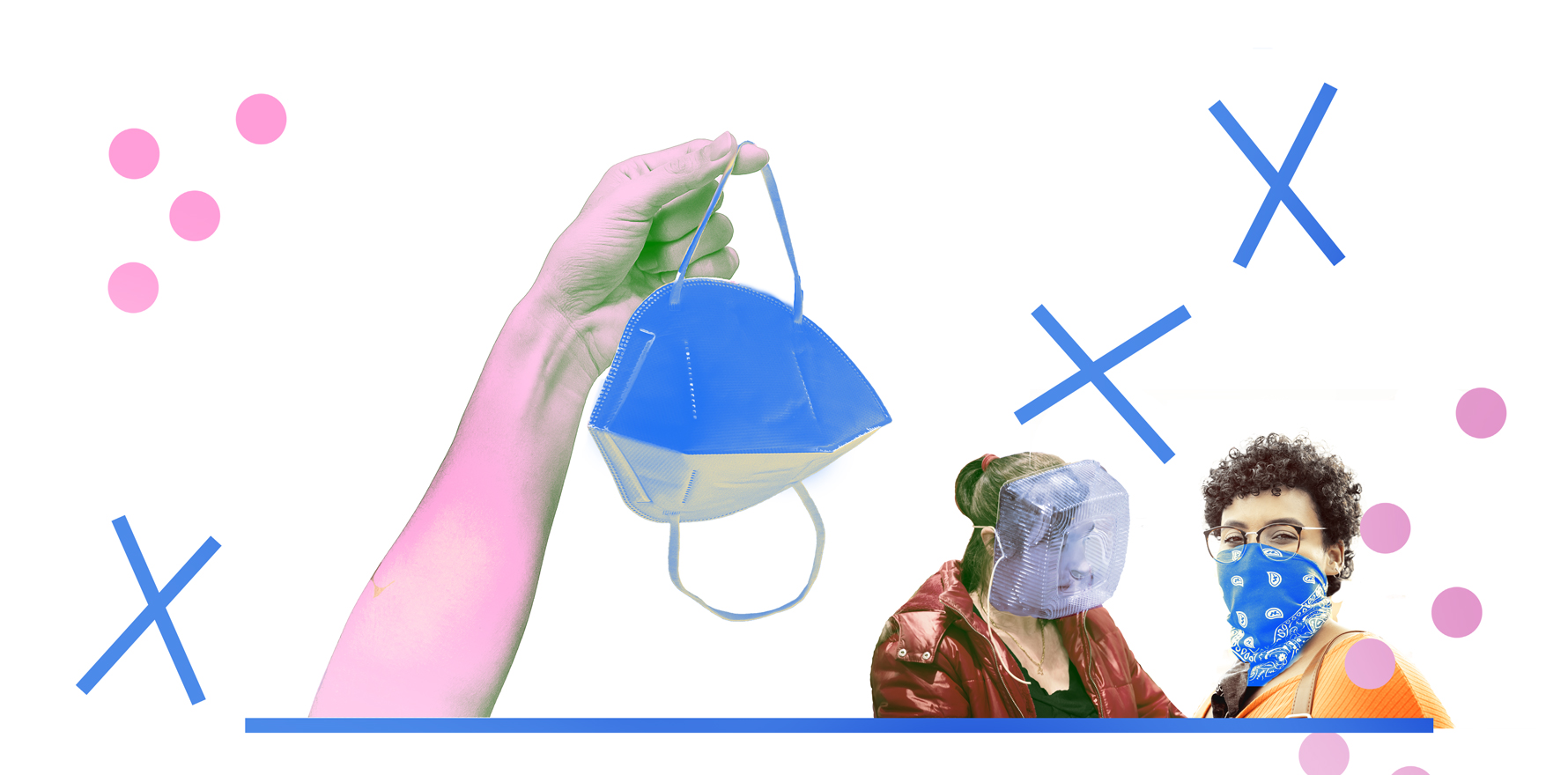

Which masks do what?

As we move into a more mandate-free approach to adapting to community covid, it’s been made clear to us that we must take responsibility for our own exposure. No one else is going to. The extreme transmissibility of Omicron argues that we should all use respirators (N95, FFP2, KN95, P2, KF94) as a first choice. It argues against reliance on cloth masks and surgical masks alone for adequate respiratory protection.

Surgical masks (and to an even greater extent, cloth masks) are neither intended nor validated to provide protection against the inhalation or emission of “fine” aerosols. Early in the pandemic, cloth masks rose to prominence based on studies that showed they blocked coarse aerosols and droplets. However, they filter only about half or less of fine aerosols (this figure varies widely depending on cloth layers).

While, as a filter, some surgical masks do arrest significantly more than half of “fine” aerosols, in use, they are notoriously leaky because they often do not seal tightly to the face. We have all observed the centimetre-wide gap at the sides of surgical masks on some people, and their failure to fit tightly around the nose. This major limitation is now largely accepted in health care settings and is slowly diffusing into the public domain.

In Australia, there are several kinds of respirators of similar functionality, based around filtering >95% of 0.3µm particles under stringent test conditions.

- N95 are US certified, have straps that go around the back of the head for tighter seal, are common in hospitals but very difficult to find for sale in shops. They come in a range of shapes (including cone, duckbill, Olson, fish). Some, designed for occupational purposes and obtained from hardware stores, have exhalation valves which means they do not protect others from your emissions if you are infected.

- P2 are Australian certified, generally have ear-loops and are increasingly available.

- KN95 are Chinese certified, usually are of the flat-fold design and have ear-loops. They are the most widely available in service-stations, home-goods shops, chemists, hardware stores and online.

- KF94 are Korean certified and are available from some chemists and online.

- European FFP2 are uncommon here.

Choosing a respirator is a case of “buyer beware”, except that the buyer, who lacks the sophisticated technology to test, cannot be aware and is reliant on a porous compliance and certification process.

With all these respirators there are issues of quality, consistency and counterfeiting, more so for KN95, particularly if purchased overseas online. Many surgical masks and respirators sold to the public are labelled in the fine print as “for particle protection”, meaning they are not “medical devices” requiring TGA oversight. Only those explicitly labelled “for medical use” and/or “intended to prevent disease transmission” are potentially subject to this.

In Australia, cloth masks are not subject to any standards, although these have been proposed in several other countries. Functionally, in the context of covid, all masks are medical devices – not fashion accessories or an occupational dust hazard.

While filtration efficacy is fundamentally important, the overall personal protection provided by any mask also depends on its seal to the face. Any leakage around the edges and particularly the nose enables aerosols to take the path of least resistance and bypass the filter and be inhaled or exhaled. Health care workers are usually quantitatively fit-tested to check that a particular respirator is a perfect seal to the face (or they should be, though GPs especially find this service hard to come by). This is not possible to replicate within a domestic setting. The best people can do is carefully adjust the straps and the malleable nose-strip and test that the shape of the mask is responding according to breathing.

While surgical and cloth masks alone cannot be advocated, the combination of a stretchy cloth mask (with nose wire) over the top of a surgical mask acts synergistically, combining the filtration of a surgical mask with the better facial fit provided by the pliable cloth and is better than either alone. This is termed “double masking” and some argue its efficiency approaches that of a moderately well- fitting respirator, although this is subjective and depends on multiple nuances.

The higher cost of respirators (typically $2-4 each – the price of a coffee) has been cited as a disincentive for their use. However, this argument presumes they are frequently disposed of, as in clinical settings. There are several recent studies showing the filtration efficacy of respirators does not decline with normal use (with one exception known to the author); rather, their working life is determined by loss of general structural integrity, failing elasticity of straps and general scruffiness. Respirators can also be decontaminated by heating (70 °C) or by other treatments available in sophisticated settings. For the public, it has been advocated that several respirators be used alternately and rotated daily, being dried in the sun between uses.

Over the past two years, studies of covid transmission have shown that, in community settings, (1) the use of any mask is better than no mask, (2) the use of surgical masks is better than cloth masks, and (3) in clinical settings, the use of respirators is better than surgical masks.

Here is a summary of mask advice you may find useful.

Covid protection or a coffee?

The best guess is that covid will morph from pandemic to outbreaks of old and new variants occurring over time in various populations, modified by season, immune erosion, vaccination and other factors. Multiple social and health adaptations will be required, including the use of good-quality masks. In addition to health care settings, respirators should be mandated under OH&S provisions in childcare, teaching, client-facing service industries, transport and where people have demonstrated high rates of infection or are critical for social stability.

A well-fitting respirator provides the highest level of personal protection against transmission of SARS-CoV-2. This efficacy has been proven for nosocomial transmission in health care settings, and this principle should equally apply to the community. As the risk of exposure to Omicron (and later variants) becomes more unavoidable in public settings, we all must lift our game and access the best respiratory protection that the cost of a cup of coffee can buy.

Euan Tovey is an associate professor and honorary affiliate senior research fellow at the Woolcock Institute, University of Sydney (these are his views), with special interests in virus transmission and sampling biological aerosols