It’s a world of debilitating pain that we’re just not equipped to handle, a Senate inquiry hears.

Red imported fire ants are aggressive, they move in large numbers, they swarm, they sting and they really, really hurt.

And experts have warned of an impending surge in the number of people who will develop severe allergies to the ants should they take hold in Australia.

Doctors will see patients “at their wits’ end,” said Ms Maria Said, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia CEO.

“They are absolutely petrified about what’s happening to them and asking for information about what to do,” she said.

“And unfortunately, all we can say to people at this point is take an antihistamine, elevate – if it’s your legs, which it often is, elevate the leg – apply a cold compress, take pain relief and rest.”

A Senate Inquiry was told that Australia did not have the capacity to deal with the number of people who would need treatment for allergy should fire ants become endemic.

The ants have marched from South America, through the US, are making forays into Europe, China, Taiwan and the Pacific islands, and they’ve so far made their presence known in Queensland and the Northern Territory.

One in three people unfortunate enough to live in an area where they’ve taken hold will be stung each year.

In their submission to the Senate Inquiry, the National Allergy Centre of Excellence and Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia revealed that a quarter of those people stung will develop allergic sensitisation, and up to 2% will have a systemic allergic reaction. That can range from hives through to anaphylaxis.

Professor Sheryl van Nunun, National Allergy Centre of Excellence insect allergy researcher, painted a sobering picture.

“So, multiple stings from one ant and multiple ants stinging. They tend to cluster, and they sting multiply, and they’re very aggressive,” she told TMR.

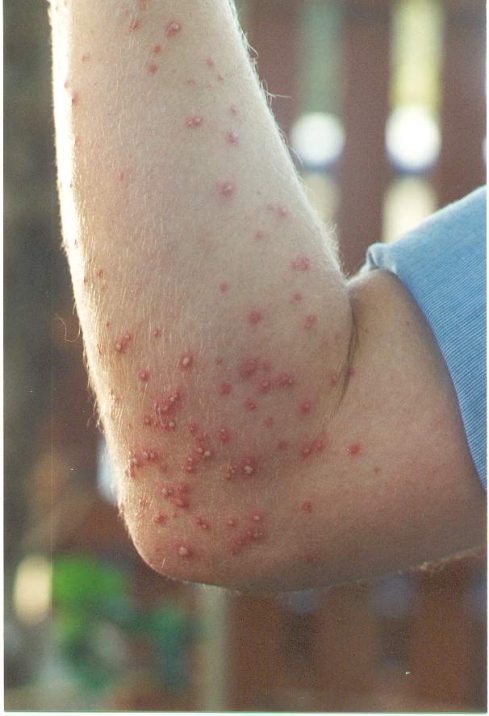

Stings – and remember, there are many – result in pustules (pictured) within 24 hours because of the venom’s alkalinity. If they burst, there is the risk of infection, septicaemia and cellulitis. Localised reactions can cause extreme pain for at least a couple of hours.

“It’s not called a fire ant for nothing,” said Ms Said.

That’s even before you start worrying about allergies. Like wasps, bees, ticks and jack jumper ants, fire ants inject venom deeply enough to force the immune system to make antibodies, causing a large local reaction, said Professor van Nunen.

This will happen to 25% of those stung, however there are variables. Not everyone who is sensitised will go on to react, immune systems are different, and the effect of the venom depends on the season (the venom is more potent in summer). Some people who have a wasp allergy can react the first time they are stung by a fire ant.

The most common allergic reaction is at the site of the sting. Swelling of around 10cm will develop at 24-72 hours, but the whole limb (usually that’s the foot or leg) can swell up, making walking impossible. And this swelling can last for seven to 10 days.

The concern is not that the rate of allergic reactions is higher (as far as we know) but that they will be greater in number because there will be so many stings. By comparison, people are stung by bees, on average, once every six years.

People who are immobile and can’t get away from the ants, and those who have allergic reactions to other insects, food and drugs are most at risk.

“But it’s other people in the community too, because it’s unpredictable,” said Ms Said.

People with existing life-threatening allergies were encouraged to live normal lives, but that wasn’t easy “if you’re petrified of the ground you’re walking on because you never know if these ants are going to be around,” she said.

Avoidance would be difficult if the ants were present in the area, both Ms Said and Professor van Nunen said. In the Australian climate, advice to wear long pants, closed shoes and long-sleeved shirts was simply impractical. Staying indoors wouldn’t necessarily keep you out of harm’s way either.

“They invite themselves in [to houses] and seek the immobile,” said Professor van Nunen.

Both emphasised the importance of community allergy education, which was “at present, substandard”, said Ms Said.

Patients at risk of anaphylaxis who were prescribed an adrenaline autoinjector “must absolutely carry it everywhere with them, whether it’s for insect or food allergy,” said Ms Said.

Ms Said said anyone in the community with food or insect allergy could be referred to Allergy and Anaphylaxis Australia for additional information and support.

Ultimately, the best option was eradication, said both Professor van Nunen and Ms Said. We’ve seen what has happened in the US, where 80% of Texans have been stung.

“One in five haven’t, and that’s the miracle,” said Professor van Nunen.

But they have access to immunotherapy. The treatment, for those who have a life-threatening allergic reaction, is a venom extract made from crushed red imported fire ants.

Professor van Nunen said there was very little supply of this available in Australia, nor enough immunologists to administer it, particularly in regional and rural areas where stings were more likely to occur.

Along with eradication attempts, Australia needed to invest in research, she said.