Expectations are high for a new clinical trial to determine whether a stem cell therapy is safe and effective for knee osteoarthritis.

A sizeable clinical trial testing a stem cell therapy for osteoarthritis has opened, encouraged by experts who say it should provide long-overdue evidence for whether or not stem cells are safe and effective for knee OA.

Led by rheumatologist Professor David Hunter at the University of Sydney’s Institute of Bone and Joint Research, the trial will evaluate whether stem cell injections in people with mild to moderate knee OA can improve symptoms and slow disease progression, with a second trial site at the Menzies Institute for Medical Research in Hobart.

There’s been no shortage of unproven, unregulated stem cell therapies marketed directly to patients and though the TGA has cracked down on clinics advertising any such products, their appeal has not diminished. If cartilage loss defines knee OA, then the regenerative potential of stem cells speaks for itself.

Yet the high hopes of patients and practitioners alike have so far fallen flat, with relatively little convincing clinical evidence produced to date for any stem cell treatments for knee OA.

“It’s fair to say many of the trial results have been trumpeted and misrepresented, in so far as that they’ve been overblown in terms of their claims, without placebo controls, without proper manufacturing controls, and very small numbers to make any sense of the results,” said haematologist Professor John Rasko, head of cell and molecular therapies at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney.

Understandably, some rheumatologists still question the merit and efficacy of stem cell treatments based on the data to date.

But others are enthusiastic about the new randomised, placebo-controlled trial, which plans to recruit 440 people and is funded by the NHMRC.

“It’s incredibly important that we have high-quality trials like this, to get the evidence that we need around efficacy and safety,” said Associate Professor Dawn Aitken, a research fellow specialising in OA at Hobart’s Menzies Institute, who is not involved in the trial.

“Because [OA] is becoming more common, people expect there’s going to be treatments for it, beyond conservative management, beyond exercise and weight loss.”

So expectations are high. The stem cell therapy on trial, developed by Australian biotech company Cynata Therapeutics, now faces “the ultimate test” after substantial preclinical research and a pilot trial, Professor Hunter said.

“A lot of the clinicians are really interested to know what the answer is: do these stem cell injections work or don’t they?” Professor Hunter said.

The complete trial period will likely run for 5 years to recruit, treat and follow-up the 440 patients involved, Professor Hunter told Rheumatology Republic.

Participants will receive ultrasound-guided intra-articular injections of stem cells or placebo on three occasions over 12 months, with follow-up assessments scheduled a year later to compare to baseline.

Professor Megan Munsie, deputy director of Melbourne University’s Centre for Stem Cell Systems and head of engagement, ethics and policy at Stem Cells Australia, said this is the first substantial trial she has seen testing a stem cell therapy for OA.

Until now, there just hasn’t been enough legitimate clinical research to advise patients what the options are or to combat unchallenged marketing from dubious stem cell clinics, she said.

Recent meta-analyses have suggested that stem cell treatments for knee OA can relieve pain and improve physical function with no severe adverse effects. However, therapies were inconsistent, the evidence poor, trials likely to be biased, and the longevity of observed effects not guaranteed.

Part of the problem has been the variety of stem cells used previously, the different dosages and treatment intervals tested, and the assortment of manufacturing processes.

Most interventions trialled have used the patients’ own cells, called autologous stem cells, which are most often isolated from a patient’s fat and reinjected into the joint. But these products are not much more than a crude cellular resuspension, Professor Munsie said.

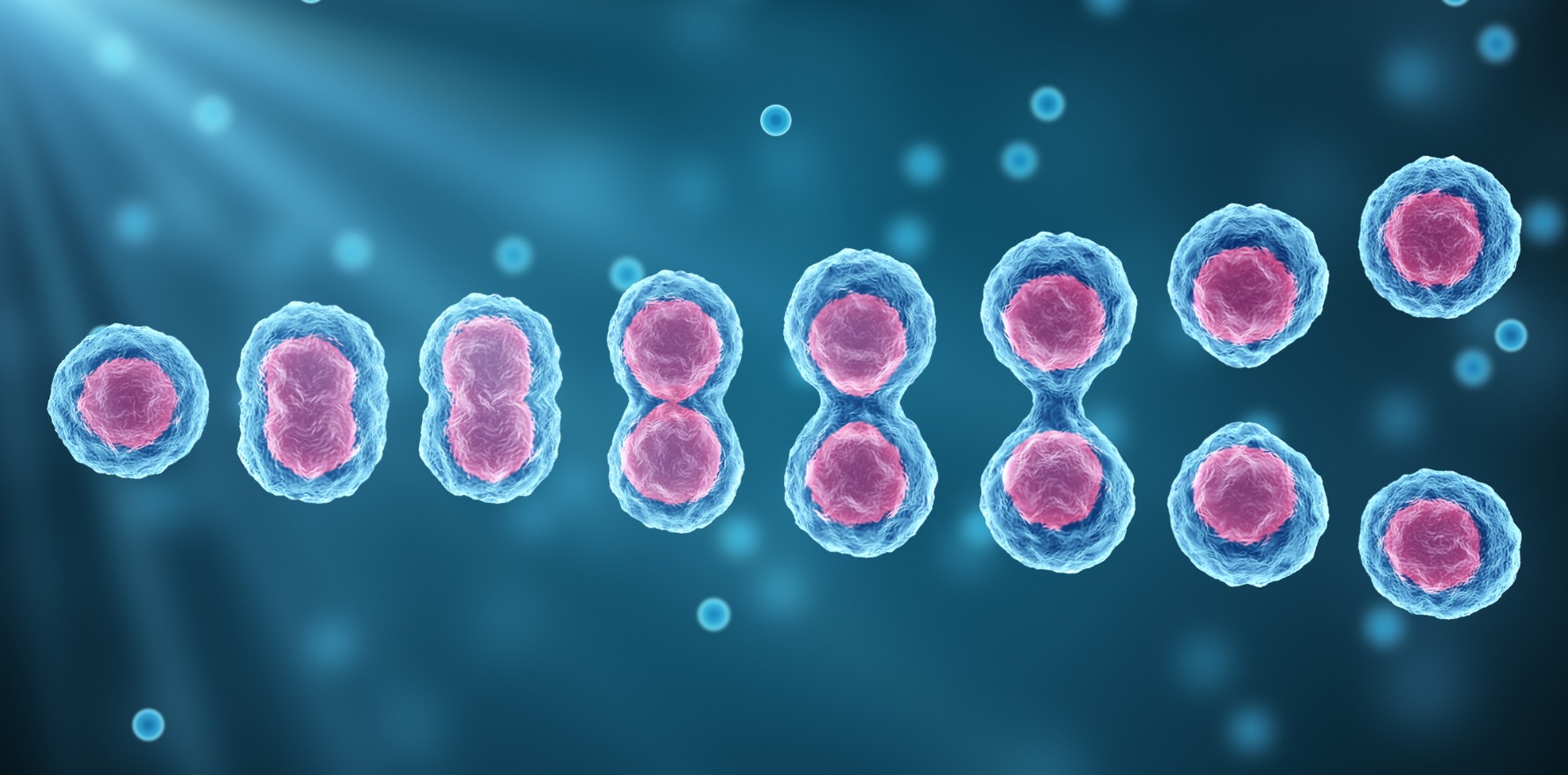

What sets this new trial apart, Professor Munsie said, is the novel strategy developed by Cynata Therapeutics which yields a “well-defined product”.

Their process uses stem cells originally derived from the bone marrow of one young donor and expanded to generate a consistent product at scale. As such, “every patient [in the treatment group] is going to receive the same thing, taking one of the uncertainties out of the picture,” Professor Munsie said.

Cynata has already tested a similar stem cell therapy (produced by the same method but still, as yet, unapproved) in another clinical trial for graft-versus-host disease, which showed they can produce a safe cellular product, Professor Munsie said.

Safety aside, efficacy is another question.

Although the use of stem cells in osteoarthritis is still considered experimental, Professor Hunter said there’s now good evidence to suggest mesenchymal stem cells work by modulating the immune response and reducing destructive inflammation within the joint, which could help facilitate the body’s own mechanisms for cartilage repair.

“By virtue of reducing that inflammation and allowing the joint’s known innate capacity for repair to take over, we would hope to at least slow some of the structural change that’s going on within the joint,” Professor Hunter said.

Outcome measures include physical assessments to assess patients’ functional performance, along with three MRI scans measuring cartilage thickness to see whether stem cells slow down cartilage loss or aid repair.

Patient-reported outcomes of pain intensity, physical activity and quality of life will also be assessed, and the proportion of patients achieving a ‘patient-acceptable’ level of knee pain at 24 months is a primary outcome for the trial.

Cost is another consideration. The cost of administering the stem cell treatment will be compared to other healthcare expenses, such as prescriptions or physiotherapy, that patients in both groups might need to manage their condition during the study period.

While Professor Hunter said he hopes to see a positive and clinically meaningful effect with Cynata’s stem cell therapy, he said: “If the trial is negative, we won’t have any shyness about reporting that.”

The short-lived effects of stem cells injections might be an issue, Professor Rasko noted.

According to Professor Rasko, who led the previous clinical trial testing Cynata’s stem cell therapy in graft-versus-host disease, it can be said “with relative certainty now” that mesenchymal stem cells injected into the bloodstream as a therapeutic product don’t last for more than a fortnight, and evidence from animal studies suggests the same is true for cells injected into joints.

Professor Hunter agreed: “At this point it’s unclear how long the stem cells are capable of lasting.”

But it’s likely, he added, that stem cells, with their immunomodulatory effects on the synovium, could have some enduring effects on inflammation within the joint.

Professor Munsie said the biggest challenge for the trial investigators will be that a lot of people will be keen to participate and those who are unable to partake in the two-site trial might be tempted to try other not-so-reputable stem cell treatments in the meantime.

“From a community perspective, it’s going to take a long time to get these results,” Professor Munsie said.

For now, Associate Professor Aitken said clinicians can encourage OA patients to try more conservative management strategies.

“We have very strong evidence to support exercise and weight loss but it’s underutilised and not well supported under our health system,” Associate Professor Aitken said.

“There should be efforts to identify new therapies, but we need to go back to what we already know, and implement that better.”