Vulnerable patients deserve a better standard of evidence than is currently offered for the effectiveness of these treatments

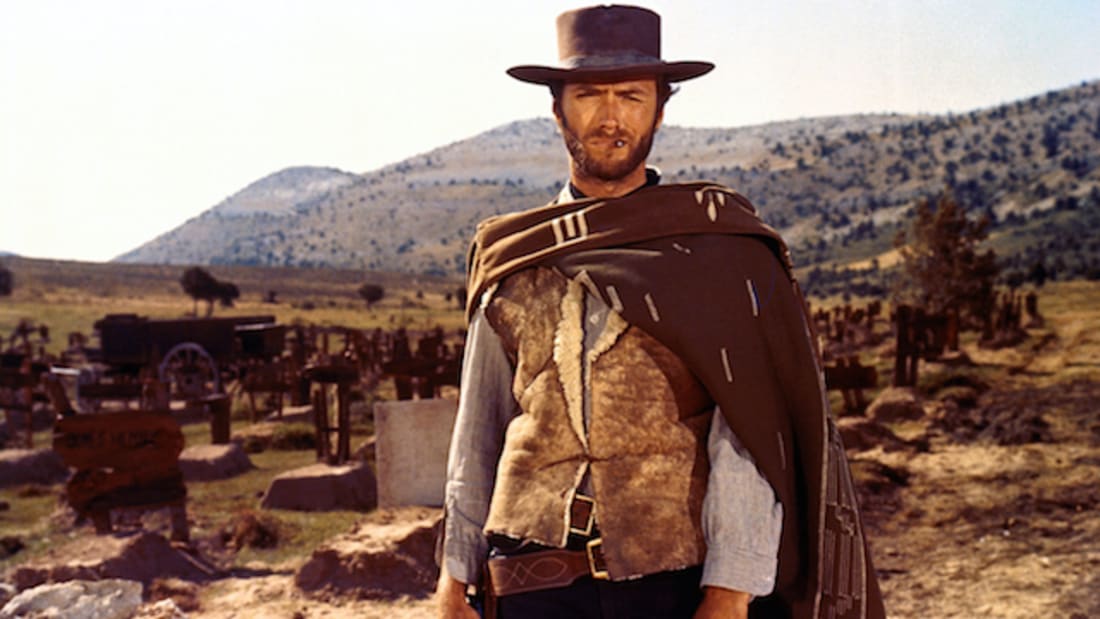

The promise of stem cells in medicine is a metropolis of glittering skyscrapers and flying cars. The current clinical reality is more like a Wild West of dusty saloons and gunslingers.

With the tighter regulation of biological products under the Therapeutic Goods Administration that came into effect this July, is it high noon for pedlars of poorly evidenced treatments?

Though the potential for tissue regeneration through stem cells is theoretically limitless – and researchers around the world are testing them on every disease under the sun – haematopoietic stem cell transplants for blood disorders, autoimmune diseases and cancers remain the only sanctioned use of stem cells in Australia.

That has not stopped a proliferation of private clinics offering to treat many other conditions – most commonly osteoarthritis, but also everything from ageing to asthma to autism – usually by injecting adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells either into tissues or the bloodstream.

While intra-articular injections for osteoarthritis are probably the least controversial of these, the Australian College of Sports and Exercise Physicians, Arthritis Australia, the Australian Rheumatology Association and the RACGP all firmly recommend against it, saying the trial evidence to date is sparse and low-quality with a high risk of bias.

Just two months ago the Australian media breathlessly reported that the Melbourne Stem Cell Centre had “conclusively … proven beyond doubt” (per the media release) that injected stem cells could regrow knee cartilage, despite the study having just 30 participants, no controls and self-reported outcomes.

These “miracle” stories were probably seen by a million commercial television viewers. Yet as Sydney University Professor of Rheumatology David Hunter told the ABC’s Media Watch in June, it was a case of PR hype unsupported by the data in the paper.

Professor Hunter, who is about to begin a trial of intra-articular injections of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells at Royal North Shore, says the current evidence does not support the widespread practice of stem cell injections.

“At present, there is plenty of opportunity for patients to be misled and to receive useless, inappropriate or dangerous treatments,” he tells The Medical Republic. “Having the TGA involved will be a lot better than the current unregulated environment. Do I think that they will fix current less scrupulous practices? Time will tell.”

Desperate patients used to have to travel to Russia, Mexico or China for such “innovative” treatments. But by 2016, according to a paper in Cell Stem Cell by Berger et al. from Sydney University, Australia had a particularly high concentration of businesses marketing stem cell-based interventions – more per capita than the US. That’s because the TGA, which regulates product not practice, excluded from its oversight the therapeutic use by a doctor of a patient’s own cells.

After agitation by professionals and academics, concerned that vulnerable patients were being fleeced and put at risk, the TGA held an extensive consultation process, and last year banned the advertising of stem cell treatments directly to consumers. Now additionally, after a one-year transition period that ended on June 30, autologous human cell tissue products are only excluded from TGA regulation if they are prepared in a hospital for a patient of that hospital.

Associate Professor Megan Munsie, deputy director of Melbourne University’s Centre for Stem Cell Systems and head of engagement, ethics and policy at Stem Cells Australia, is among the academics who pushed for tighter regulation. She says while she welcomes the tougher stance, she was surprised by the hospital exclusion.

“That distinction between hospital and non-hospital practice wasn’t part of the consultation processes,” Dr Munsie tells The Medical Republic. “It’s still a manufactured product and surely the TGA is a better assessor than the governance committee of the hospital.

“If it’s happening within a hospital then it’s not the TGA’s responsibility. That really concerns me – because whose responsibility is it then? The hospital has to be accredited, whether public or private, but this is a very speciality niche and I can imagine that some hospitals may not be well equipped to explore the claims made by a company or practitioner who’s saying ‘I’ve been doing this for years, look at my portfolio of patients and fabulous results’.

“I think the TGA are trying to address this problem as best they can, but we’ll need to keep monitoring to make sure it has the effect of protecting patients from possibly dangerous and exploitative practices. This isn’t just TGA’s responsibility. The professional bodies, medical boards, colleges need to [be vigilant] as well.

“I don’t think we should be leaving it to the market to correct itself and I certainly don’t think it should be left to consumers to navigate this.”

Doctors rarely dob each other in, and patients are often reluctant to complain, whether out of embarrassment or just lack of energy when fighting an intractable condition, Dr Munsie says.

Ken Harvey, Associate Professor of Public Health and Preventive Medicine at Monash University and President of Friends of Science in Medicine, is a little less charitable about the TGA, given that it relies on industry for funding and on complaints rather than pro-active surveillance.

“They’re pathetic,” he tells The Medical Republic. “They have far more interested in protecting industry than the consumer. Until they do some prospective evaluation of ads and clinics, or we get more resources to put in complaints, nothing will happen.”

He says the flaw in the new regime is that unproven treatments can still fall outside the regulations as long as they are not advertised, but offered in the privacy of a consulting room.

Dr Harvey says he could find only one complaint upheld so far for stem cell advertising: the Advanced Hair Studio. Yes, as in Warnie.

He says he and his colleagues don’t want to stop innovation, but that it needs to be done within the bounds of clinical trials so that we end up knowing whether it works or it doesn’t.

“That there are the cowboys just offering it to vulnerable patients for large amounts of money is appalling, it’s not advancing medical practice at all and it should be stopped. But of course, there’s lots of money to be made and who’s going to stop it?

“AHPRA is a weak regulator too. Investigations take years and have soft outcomes. They speak softly, don’t produce harsh penalties, try to fix things by negotiation.”

Since the new rules came into effect there has been a spectrum of responses from private clinics. The Medical Republic took a Google tour around Stem Cell Town and found some tumbleweeds – an established practice in Sydney’s inner west that now has a disconnected phone number and a not-found website, for example – but also plenty of signs of life.

Chatswood Stem Cell Clinic on Sydney’s north shore answers the phone but has no website advertising its services or products. In response to emailed questions it said it took autologous cells from blood and bone marrow, “using commercially available kits”, for use on knee and hip joints, tendon tears and facet joints. The clinic said nothing had changed since June 30.

At the website of Macquarie Stem Cells, the most prominent provider with branches in four cities, and usually the top result of any Google search for stem cell treatments, everything looks intact.

But place a query on the contact page and you are told: “Thank you for your enquiry, our treatment is on hold … Unfortunately we are showing you this automated message to inform you that Stem Cell Therapies are paused as of 30th of June 2019, due to new TGA regulations … These actions are beyond our control and enforced by the government. These regulations apply to all stem cell clinics in Australia. In the meantime, we will be working towards the new regulations.

“We will contact you, once we can resume stem cell treatments, this may take a few months or possibly up to three years.”

Founder Dr Ralph Bright told The Medical Republic via email that Macquarie was part of a group, Sculpt Cosmetica, which had taken the decision to suspend his practice.

“Any rule or regulation will be better or worse for some, fair for some and unfair for others. We have given our opinions to help shape these changes and we accept the group decision.

“I enjoy people, medicine and stem cells. There are many options for how we move forward in this group while continuing to respect the group. We are looking at all the options and preparing pathways to satisfy those options.”

He didn’t respond to further questions.

From a search for “stem cell treatments Australia”, The Medical Republic clicked on a Google ad for Cellf Solutions in Perth, which offers injections of human placenta cells and intravenous vitamins as well as a “cell therapy” treatment it describes without naming it.

“1. Harvesting: A simple fat graft (lipoaspirate) is undertaken under a local anaesthetic. 2. Separation: All harvested material is then deposited into our state of the art closed system for washing. 3. Activation: The cells are separated from fat cells in high-speed centrifuge within the system where centrifugal force separates the dormant stem cells. 4. Delivery: A specialist will then inject the cells site-specific as discussed in a prior consultation. The average time for the procedure is 3.5 hours and is completed on the same day.”

The TGA is looking into whether this constitutes advertising.

Cellf director Lianne Gianoli says Cellf has devoted time and resources to complying with the new regulations, including by moving into a hospital (it gives its address as Southbank Medical Suites). She denies that Cellf uses stem cells, saying it uses stromal vascular fraction for tissue regeneration.

Stromal vascular fraction contains mesenchymal stem cells, and in any case the new regulations apply to all autologous human cell and tissue products, the TGA says, not just stem cells. Alerted by The Medical Republic to the remnant “stem cell” reference in item 3 above, Cellf edited it out.

The MasterCell Stem Cell Centre on the Gold Coast is less coy, touting itself as a “state of the art stem cell centre of excellence [offering] a number of exclusive protocols which are now being validated by clinical trials. We are able to offer patients access to cutting edge adipose and bone marrow stem cell therapy for an array of objectives, whether you require treatment for a crippling condition or you may be looking to enhance your general health and longevity of life.”

On its website it promotes treatments for MS, Parkinson’s, dementia and autism, as well as two dozen autoimmune and degenerative diseases; it also has a “cancer support centre”.

Brisbane’s ASC Treatment offers facial injections of stem cells “to restore a youthful and radiant appearance”, and intravenous stem cell reinfusions in which “the stem cells will seek out damaged parts of the body to carry out regeneration and repair functions. This has resulted in reinvigoration, reinforced immune systems, and general wellness in patients.”

These are just a few of the businesses offering stem cell treatments around Australia.

Even though we couldn’t resist the cowboy motif in our introduction, The Medical Republic does not suggest that any of the practitioners is acting out of anything but good faith. It is perfectly plausible that each has seen evidence that satisfies them or is convinced that the theory must hold in reality.

But vulnerable patients, especially those who do not have the luxury of time, deserve a better standard of evidence than “anecdata”.

Adverse outcomes from stem cell interventions around the world have included cancers, ectopic tissue growth, infections, strokes, cardiac arrests and blindness. (For a list of acute complications and deaths reported in the scientific literature and mass media, see Bauer et al.’s 2018 paper in Stem Cells Translational Medicine last year.)

Last month the FDA won a federal court ruling that allowed it to issue a permanent injunction against the Florida clinic U.S. Stem Cell, which blinded three patients by injecting stem cells into their eyes to treat macular degeneration.

Health Canada has recently written to 36 clinics across the country requesting that they stop doing procedures until they have regulatory approval. It is publicising the cautionary tale of a Canadian man who went to Portugal and spent about $50,000 to have nasal cells injected into his spine, where an injury had left him partially paralysed. Instead of regaining his mobility, he started losing function in his arms thanks to a tumour of nasal cells on his spine.

Australia has not had any outcomes like these, but there has been one fatality: Sheila Drysdale, who suffered hypovolemic shock after liposuction at Macquarie Stem Cells. While her death did not directly result from the injection of stem cells, she was there to be treated for dementia – an intervention with no supporting evidence. Dr Bright was thereafter restricted by AHPRA to treating osteoarthritis.

Dr Munsie has heard all the conspiracy-theory arguments as to why these therapies are not accepted: the pharmaceutical companies want to keep selling you drugs, the surgeons want to keep replacing your knees, doctors want you to stay ill so you keep seeing them, and so on.

That logic, of course, fails to appreciate the vast array of medicines and therapeutics that have been painstakingly trialled and approved.

“We do have a rich arsenal to help and support people have a better quality of life for an enormous number of conditions, and we want more safe and effective treatments for those patients with unmet need,” Dr Munsie says. “We shouldn’t have to throw out the rulebook and say we don’t need evidence or reproducibility or independent oversight and scrutiny.

“Patients who have made the challenging decision to pursue these treatments have been through the ringer. They come, some of them, from a deeply cynical place. They may have had some poor medical experiences that feed this conspiracy-type thinking.

“So when they find someone who doesn’t say ‘sorry, but there’s nothing more we can do’, or ‘we can’t cure you’, but says ‘well of course I’ll try to help’, it’s pretty compelling. When people are at a very low ebb they’re very vulnerable to this kind of presentation.

“That is why it’s very necessary for the TGA and others to take a strong stance here, so the demarcation of what’s acceptable and what’s not is not just left to the patient to try to navigate.

“The staff I’ve worked with at the TGA are trying, and after eight years of asking for change I’m thrilled that someone is listening. It’s progress.

“I fear that the hospital exemption is a loophole. But let’s wait and see.

“Hopefully it won’t take another death and countless inquiries to rectify it. There’s a greater level of awareness now.”