To close chronic health gaps, prevention must be the focus of the advice it provides to government.

For the land of the fair go, Australia has work to do on our health. Although the average Australian’s life expectancy is very high, that’s not true for everyone.

Indigenous Australians, and Australians with little formal education, can expect to die about eight years younger than their fellow citizens. People who live in rural areas will die about two to three years earlier, on average, than people who live in cities.

And because chronic diseases create most of these gaps, these disadvantaged people will spend more years living in ill health than other Australians.

These statistics don’t begin to capture the immense suffering behind the numbers, or the deep injustice of gaping health gaps in a wealthy nation like ours.

The government has promised to set up a Centre for Disease Control (CDC), which will tackle both infectious and chronic disease. A new Grattan Institute report shows how it can be set up to drive down rates of chronic disease. This will help reduce health disparities, especially if the CDC builds equity into its DNA.

Chronic disease lies at the heart of health inequities

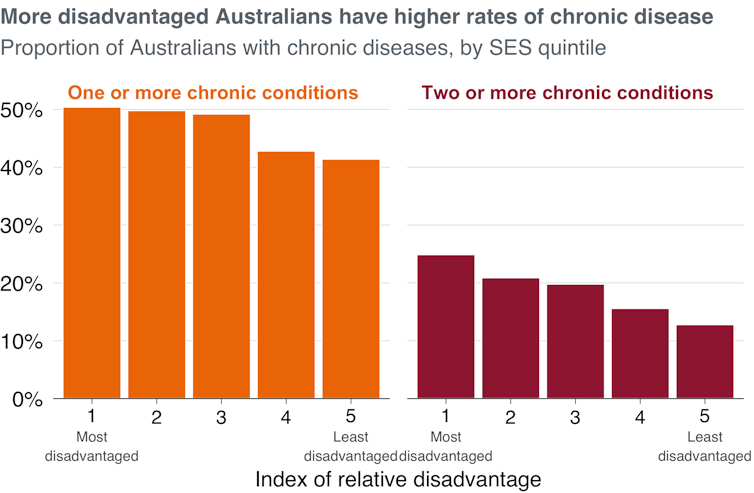

Much of the life-expectancy gap between the most and least disadvantaged Australians is explained by skewed rates of chronic disease.

The most disadvantaged fifth of Australians are about 20% more likely to be living with one chronic disease, and about twice as likely to be living with two or more, compared with the most advantaged fifth of Australians.

It’s estimated that about 80% of the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians is caused by chronic diseases.

Gaps in health start before sickness

Some chronic diseases are difficult to prevent. There is little we can currently do to stop the onset of type one diabetes or cystic fibrosis, for example.

But other chronic diseases are the result of risk factors such as smoking, alcohol abuse, or being overweight or obese, which we can change.

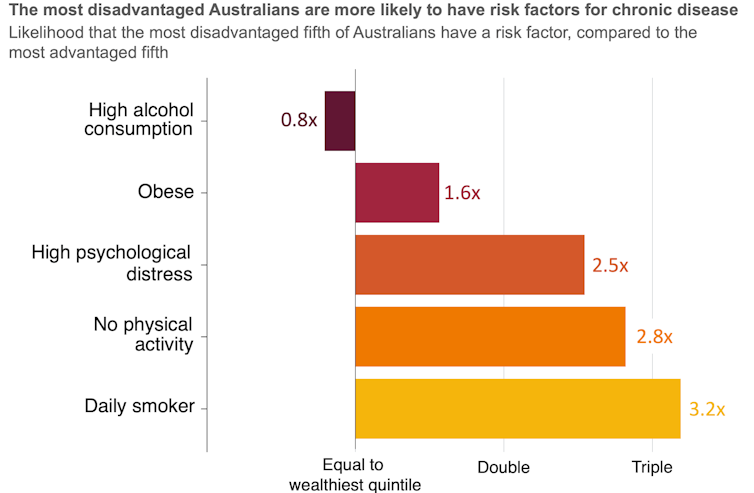

These so-called modifiable risk factors are the cause of about 40% of the chronic disease burden in Australia. And, like chronic diseases, rates are significantly higher among disadvantaged Australians.

Compared with the most advantaged fifth of Australians, the most disadvantaged fifth are about 60% more likely to be obese, more than twice as likely to have high psychological distress, almost three times as likely to do no physical activity, and over three times as likely to smoke daily.

This means inequity is already baked in well before people get ill.

Isn’t being healthy a choice?

Modifiable risk factors are sometimes branded as “lifestyle choices”. But this glosses over the fact our choices are heavily influenced by environmental and social factors.

For example, more disadvantaged Australians are more likely to find it hard to get or afford sufficient healthy food, which increases the risk of obesity. The increased and often chronic stress that disadvantage brings is associated with smoking more, and may have links with obesity.

Disadvantage is also intertwined with fewer educational opportunities, and education is strongly linked to health because it provides people with better knowledge of health and healthy behaviours. It shapes employment opportunities and can provide a stronger sense of personal control, which helps people make healthier choices.

Many modifiable risk factors may seem like choices, but the causes are often structural. There’s little Australians living in disadvantage can do about these influences, but they all increase the chance of modifiable risk factors, and sickness.

A CDC has a chance to reduce health gaps

The proposed Australian Centre for Disease Control, promised by the Albanese government, is an opportunity to tackle these structural barriers.

The centre has a big job to do. Australia has fallen behind our peers when it comes to prevention. As our report shows, we spend about 2% of the health budget on public health, which is less than one-third of what Canada spends, less than half of what the United Kingdom spends, and far below the OECD average.

While many other countries have introduced sugar taxes or taken action to reduce people’s intake of salt and trans fats, Australia’s prevention progress has largely stalled.

Our report shows that to have an impact, the CDC must be set up for success, with independence and the right role and resources. And the federal and state governments must make a new funding deal to make the investments the centre recommends.

A focus on fairness

Reducing risk factors across the population would have a big impact on health inequity. But to make the biggest gains, the communities at highest risk should be the focus. The CDC should understand who those communities are, and what will work for them.

One of its central roles should be providing technical advice to Australian governments. This advice must take equity into account.

When the centre looks at what works in prevention, it should consider who will benefit. Initiatives that disproportionately benefit disadvantaged groups should be valued more highly.

When the centre advises government on progress and targets, it should reflect not just how the average Australian is going, but also the status of groups that have traditionally been left behind.

To help the centre understand health disparities and the perspectives of people who experience them, the staff, leadership and culture of the centre should be diverse and inclusive, representing the broader community. And the centre should also listen to different groups that face the biggest barriers to good health, using a range of consultation and engagement methods.

Narrowing the health gap that divides Australians won’t happen overnight. And not all the structural barriers that create health inequalities can be solved by another government agency.

But for too long, these gaps have received too little attention. A strong, equity-focused CDC can help ensure that, when it comes to their health, all Australians get a fair go.

This article was originally published by The Conversation.

Peter Breadon, Program Director, Health and Aged Care, Grattan Institute and Lachlan Fox, Associate, Grattan Institute