Behind this commonly cited statistic is one paper containing some very big flaws.

There’s a common claim splashed around whenever we talk about medical issues — that medical error is the third leading cause of death in the United States.

It is so ubiquitous that you can find it quoted in TV dramas, thrown around in news stories, and constantly referred to online every time anyone wants to make a point about how bad the healthcare system is.

And it’s quite a persuasive argument for several reasons. Everyone agrees that the medical establishment sometimes harms people. If you don’t know how these things are calculated, the idea that medical errors could cause a lot of death is not itself ridiculous. We’ve all heard tales of lawsuits galore targeting bad doctors, naughty nurses and other problematic professionals in the healthcare space.

Fortunately, the statistic is completely ludicrous. Medical error is a serious issue, and is the focus of an enormous amount of research and quality improvement in hospitals. However, it is nowhere near the third leading cause of death in the United States – it probably doesn’t even make the top 15.

The science

There’s a bit of history here. Since the late 90s, people have been looking into the idea of medical quality improvement. The thought process is simple: there are places where the healthcare system fails in a predictable, systemic way. Perhaps the most common example of this is hand washing, because we know that doctors and nurses don’t wash their hands in 100% of the situations that they should (it’s more like 75-90%) and if you can bring that number up even a little bit you are likely to prevent infectious diseases that can cause a great deal of patient harm.

And this is how we get the hand washing programs that are ubiquitous across almost every hospital in high-income nations these days. We identified a possible issue, and over the last two decades have invested a lot of time and effort into improving hand hygiene in healthcare settings.

But by the mid-00s, this idea had morphed into a much less reasonable refrain. Instead of there being places in medicine that could potentially be improved, people had started talking about medical issues being the direct cause of people’s deaths. Not errors in the way that we traditionally think of them, mind you – the idea is that systemic issues such as whether a hospital has the most up-to-date hand washing stations are directly causing mortality.

This brings us to the paper that estimated the number you’ve heard about in the news: a 2016 commentary piece in the BMJ. In this paper, the two authors aggregated a number of studies that looked at deaths potentially related to medical mistakes, worked out the average rate of such issues in the four studies that they found, and applied this to hospitalisation statistics in the US.

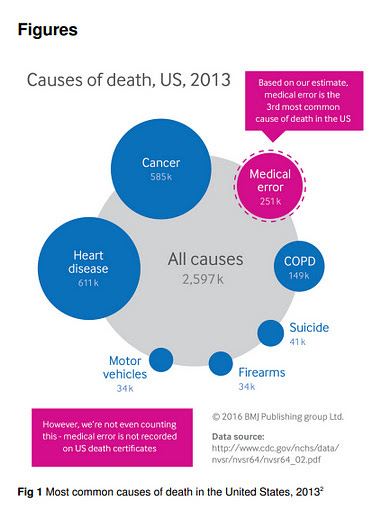

With about 35 million hospitalisations in the US in 2013, and a rate of 71 deaths per 10,000 hospitalisations related to medical errors in the four studies they reviewed, the researchers estimated that the total number of deaths would be 250,000 each year. That put the figure firmly in third place for leading causes of death in America, trailing behind cardiac disease and cancer (this was done pre-covid; depending on year it would now be either third or fourth).

Credit: BMJ, from the paper cited

The implication of the paper is clear: an individual living in the United States is more likely to be killed by a medical error than by guns, road accidents, poisonings, or suicide combined. That’s terrifying.

Luckily, the number is definitely wrong.

The issues

The first problem with the study is very simple: many of the numbers extracted from the four included papers are incorrect. This is rather alarming, because those numbers themselves are the genesis of the entire estimate.

For example, the BMJ authors link to this 2004 study, and say in their table that there were 389,576 deaths considered “due to a preventable event”. However, I cannot find that number anywhere in the paper, and the figure that I can find is more than 100,000 deaths lower:

“Of the total of 323,993 deaths among patients who experienced one or more PSIs from 2000 through 2002, 263,864, or 81%, of these deaths were potentially attributable to the patient safety incident(s).”

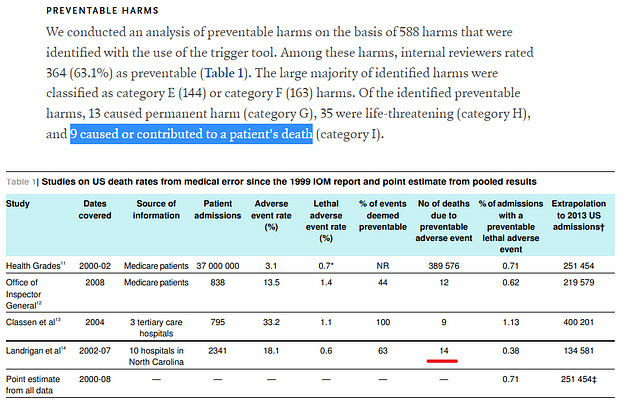

Many of the numbers in the BMJ paper seem to be incorrect. The Classens et al. paper reports eight deaths potentially related to medical errors — the BMJ piece has instead given nine. The Landrigan et al. paper in the New England Journal of Medicine says “Of the identified preventable harms … 9 caused or contributed to a patient’s death (category I).”, but the BMJ table has 14 deaths listed instead.

Top — screenshot of Landrigan et al, NEJM 2010. Bottom — screenshot of Makary and Daniel, BMJ 2016.

So the numbers themselves aren’t very good, which is something of a bad sign.

However, sloppy numbers aside, there are lots of other issues with the “Third leading cause” claim. Remember, the authors of the BMJ paper took these studies and applied the results to every hospitalisation in the United States.

That is just ridiculous.

The four studies that are included here are, in order:

- Review of all patients receiving Medicare in the US from 2000-2002

- Review of smaller sample of Medicare patients

- Review of adults admitted to three unnamed large hospitals

- Review of adults admitted to 10 hospitals in North Carolina

None of these are remotely comparable to the US population as a whole. Medicare recipients are by definition older and/or disabled. A small sample of hospitalised patients in one state are obviously not representative of the entire country. And even if we ignore all these problems, the authors have multiplied the rate of death by the total number of hospitalisations in the US, which includes children, but all of these studies were conducted in adults.

In short, the extrapolation is absurd. You can’t simply infer from these heavily biased samples to the entire population of the US, it makes no sense at all.

And somehow, that’s not even the end of the story about the issues with this paper.

More issues

I touched on this before, but the final issue here is the question of what constitutes a medical error.

There are clear examples where clinicians have caused deaths that few people argue about – if an obvious diagnosis is missed because of misplaced test results, for example, or where a surgeon’s hand slipped and someone passed away. And, if you read the BMJ paper itself, these solid, definite cases seem to be what the authors are talking about:

“We have estimated that medical error is the third biggest cause of death in the US and therefore requires greater attention. Medical error leading to patient death is under-recognized” (BMJ, 2016, bolding added)

These are deaths, you would imagine based on reading the study, that are “due to” or “caused by” medical error. Even the headline of the paper states this in no uncertain terms.

But that’s simply not what the included research estimates. The four studies used various retrospective grading tools to look at patient records and decide whether they thought there was a medical error of some sort, and then made an assessment as to whether this error might have contributed to a person’s death.

For example, the large Medicare study from 2004 estimated that most of the medical issues that they reviewed were due to what’s called “failure to rescue”. This concept is defined as the failure of medical services to respond adequately to a complication during medical care, and can encompass everything from too low or high a dose of antibiotics, to forgetting to order a blood test. The authors of this study used a software package to identify whether patients were likely to have had an issue such as this, using routine codes that were considered to be related to medical errors.

The problem is that this is very subjective and mostly assessable in hindsight — it’s easy to say on reviewing a person’s chart that they might’ve done better on different medication, but whether that really does constitute a medical error is complex and not nearly as cut and dried as the BMJ paper suggests. Even worse, here we’re talking about a decades-old algorithm arbitrarily assigning a code to a patient’s medical record.

Indeed, none of these four included studies ever made the claim that medical errors caused the deaths they reviewed. The four included papers all used language like “potentially contributed to” or “may have impacted”, because they did not assess causality per se – they simply noted that people had had some form of medical error and then died, without attributing the death to the error.

This makes the top-line estimate from the paper quite obviously ridiculous. The BMJ paper with its “third-leading cause” claim implied that around one-third to half of all hospital deaths are directly caused by medical mistakes. Yes, you read that right — 30-50% of all people who die in hospital would have to die directly from medical errors for this to be true.

But this idea is completely contradicted by higher-quality evidence. A careful British review of randomly selected patients from across the country found that only 3.6% of deaths in hospital were likely to be related to an avoidable medical issue. This paper, rather than simply assuming that anyone with a specific disease code had experienced a medical mistake, carefully reviewed each patient record and made a decision as to whether there had been a medical error, and whether that error was likely to have contributed/caused the death.

In other words, based on careful assessment by trained, unbiased clinicians, the rate of death caused by medical errors is likely to be at least 10x lower than the estimates produced in the 2016 BMJ piece. This would equate, in America, to about 20-30,000 deaths related to medical issues, putting the figure somewhere around the 16th-20th leading cause in the US depending on year.

Which brings us back to the start: that’s still a big number. It’s debatable whether all these deaths are avoidable, exactly – the British review noted that the number might’ve been reduced by improving the visibility of “do not resuscitate” orders, for example – but it’s important to note that 20-30,000 remains quite high. Remember, in theory these deaths should all be preventable, to an extent, and ideally we wouldn’t have anyone at all dying from preventable medical problems.

That being said, the idea that medical errors are a key leading cause of fatality in the United States and elsewhere is simply incorrect. Yes, medical error is a problem, and no one would ever deny that we should work hard to fix that. But medical errors clearly aren’t the third-leading cause of death in America.