Researchers have identified 19 medications that may cause more harm than benefit – and for some they provide safer alternatives.

Australian experts have developed a list of 19 medications that may cause more harm than benefit for older patients.

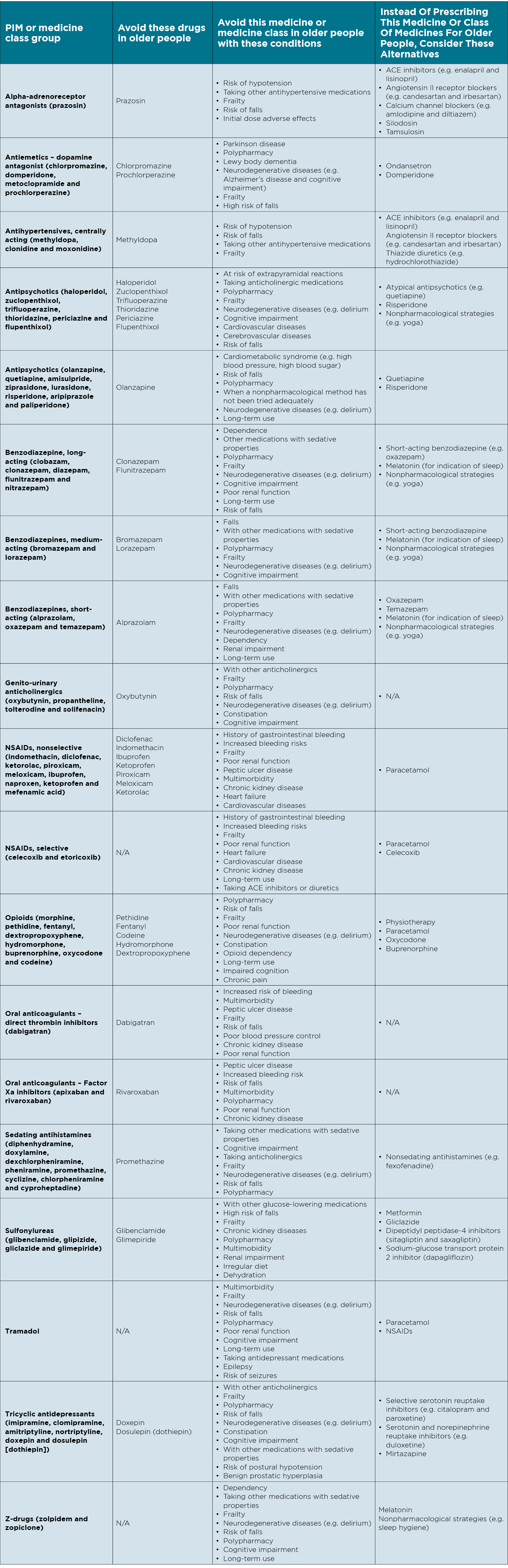

And, importantly for 16 of these potentially inappropriate medicines, these experts also suggest alternatives, according to a consensus statement published in the Internal Medicine Journal.

Following the collaboration of a team of 33 Australian experts from multiple specialties including geriatrics, general medicine, pharmacy, clinical pharmacology, general practice and epidemiology, the recommendations include avoiding the alpha-adrenoreceptor antagonist prazosin, due to the risk of hypotension and falls, and instead consider ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers or silodosin and tamsulosin.

The centrally acting antihypertensive methyldopa should also be avoided in favour of ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers and thiazide diuretics.

The researchers recommended avoiding olanzapine due to risks of cardiometabolic syndrome, falls and neurodegenerative diseases such as delirium, in favour of quetiapine and risperidone.

When it came to NSAIDs, celecoxib was the recommended alternative along with paracetamol.

And for opioids, oxycodone and buprenorphine were suggested as safer alternatives to hydromorphone.

Gliclazide was the only sulfonylurea to be listed as a safer alternative to other sulfonylureas – glibenclamide, glipizide and glimepiride.

The researchers suggested tricyclic antidepressants doxepin and dosulepin (dothiepin) be avoided in favour of SSR inhibitors and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and mirtazapine.

While he welcomed the list as a “very helpful and practical resource”, Professor Mark Morgan, chair of the RACGP’s Expert Committee – Quality Care, noted that in the list of safer alternatives, paracetamol featured frequently as an alternative to NSAIDs or opioids for analgesia.

“While this might be true from a safety perspective, it should be noted that the evidence of efficacy of paracetamol for some painful conditions is limited,” he said.

“Low back pain and osteoarthritis are examples where many patients don’t see a benefit from paracetamol.”

Lead researcher Dr Kate Wang told Rheumatology Republic the list was not intended to alarm clinicians into thinking they needed to automatically change patients to alternatives provided or stop medications altogether.

“Definitely not – it’s just a recommendation for doctors and clinicians to take a look at whether or not [the medication is] appropriate,” she said.

“Every patient is unique. Regular reviews and reducing to a lower dose where possible to reduce potential risks will hopefully lead to good clinical outcomes.

“It’s definitely not a substitution for clinical knowledge.”

Dr Kate Wang, said the list was helpful for clinicians to identify medications that have higher risk of negative clinical outcomes, including hospitalisation and death.

“They should only be used in circumstances where there is a clear need and not an effective and lower-risk alternative available,” said Dr Wang, from RMIT’s School of Health and Biomedical Sciences.

“The Australian setting is unique and it is vital that we have our own, up-to-date resource.”

These lists of high-risk medicines are especially important for older people, who often need multiple medications to manage their conditions. Between 20–70% of older people are prescribed at least one potentially inappropriate medicine, according to the study.

Australia’s existing potentially inappropriate medicines list was developed 15 years ago, and there have been many changes to medications available in Australia since then.

“We found that the lists in other countries were only partially applicable in Australia due to differences in medication availability, what clinicians tend to prescribe, clinical practice guidelines and the healthcare system,” said Dr Wang.

Professor Morgan said that while he saw the list as a helpful resource, it would be “more helpful still if there was a layer of evidence-synthesis underpinning the various recommendations so we could trust they are based on the best available information, rather than just collected wisdom from multiple experts”.

“I hope there is opportunity to build on this initial work to ensure the alternatives that are suggested are the best available,” he said.

One way to implement the collected wisdom presented in this paper is by computer decision support, Professor Morgan suggested.

“CDSS could play a role in alerting GPs who are about to prescribe one of these medicines to a patient that fits into one of the high-risk groups,” he said.

“Alerts need to be concise, relevant to the specific patient and offer alternative, evidence-based strategies.”

(Click to open full size version)