The first Australian clinical care standard for opioid stewardship in acute care also discourages slow-release delivery.

Doctors can hopefully expect more detailed discharge summaries for post-operative patients, with a new clinical care standard outlining clear instructions for clinical handover of patients who have been started on opioids for acute pain.

Launched yesterday, the new standard from the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care looks at opioid analgesic stewardship in acute care settings, particularly acute post-operative pain.

It does not cover management of chronic non-cancer pain, cancer pain, treatment of opioid use disorders or patients presenting to hospital with major acute trauma.

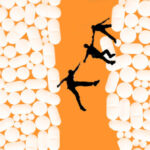

The commission said that up to 70% of Australian hospitals report sending people home with “just-in-case” opioid analgesics, and that anywhere from 4% to 23% of patients who undergo surgery end up taking opioids prescribed for post-operative pain for longer than three months.

“The duration … of the first opioid analgesic prescription, rather than the dosage, is more strongly related to misuse in the early postoperative period, with each refill and week of opioid analgesic prescription associated with a large increase in opioid misuse among opioid-naive patients,” the standard reads.

The standard itself is arranged around nine “quality statements”. These touch on shared decision making, acute pain assessment, risk-benefit analysis, pathways of care, appropriate opioid analgesic prescribing, monitoring for adverse effects, documentation, review of therapy and transfer of care.

Given that the standard is largely focused on opioid prescriptions initiated in a hospital setting, the most relevant section for primary care doctors is the quality statement on transfer of care.

It asks for health services to ensure “prompt communication of a clinical handover summary” to the GP that includes information on the cause of the pain for which an opioid analgesic was prescribed, the dose prescribed or recommended on discharge and a medication management plan with recommendations for reducing and ceasing the opioid.

“Whenever the patient is discharged back to the community, adequate communication to the patient and their GP about the plan for the medicines is essential,” said Conjoint Professor Anne Duggan, Commission Chief Medical Officer.

“This clinical care standard is asking that we take opioid analgesic stewardship as a shared responsibility.”

One of the more controversial aspects of the standard is that it discourages the use of slow-release opioids for patients not already on them, according to anaesthetist Conjoint Associate Professor Jennifer Stevens, who helped write the standard.

The goal is to match opioid delivery to periods of increased activity and pain, Professor Stevens said.

“The idea is that you use simple analgesics as your background and then you use the opioid as immediate release under the control of the patient as much as possible to match those times of increased pain,” she said.

“What that does is reduce the overall number of milligrams of opioid, which then reduces the side effects while still getting the same result.”

The standard expressly states that there is currently no evidence to support the use of modified-release opioid analgesics for acute pain, and emerging evidence to show that its use is instead problematic.

“As prescribers, doctors have an ‘opioid-first’ habit that we need to kick,” Professor Stevens said.

“Compared to many European and Asian developed nations, Australia places a high reliance on using opioids as first-line analgesia, despite evidence those countries with significantly lower reliance do not have poorer pain outcomes.”

Professor Stevens also clarified that she was not advocating for complete cessation of opioid prescribing, and that there are also issues with under-dosing patients.