Their lives have been shaped by a saga of grotesque medical negligence, but Australian thalidomide survivors are now tentatively welcoming a victory.

Her body is the physical manifestation of a drug pregnant women should never have been given, but Lisa McManus has nothing to hide.

What you see is what you get.

Born to a mother who took medication containing thalidomide while in the early stage of pregnancy, the 57-year-old is living proof of drug development gone wrong.

German company Chemie Grünenthal made thalidomide, and it became the active ingredient in tablets that reached European markets in 1957, sold as a sedative to treat insomnia, headaches, nausea and morning sickness during pregnancy.

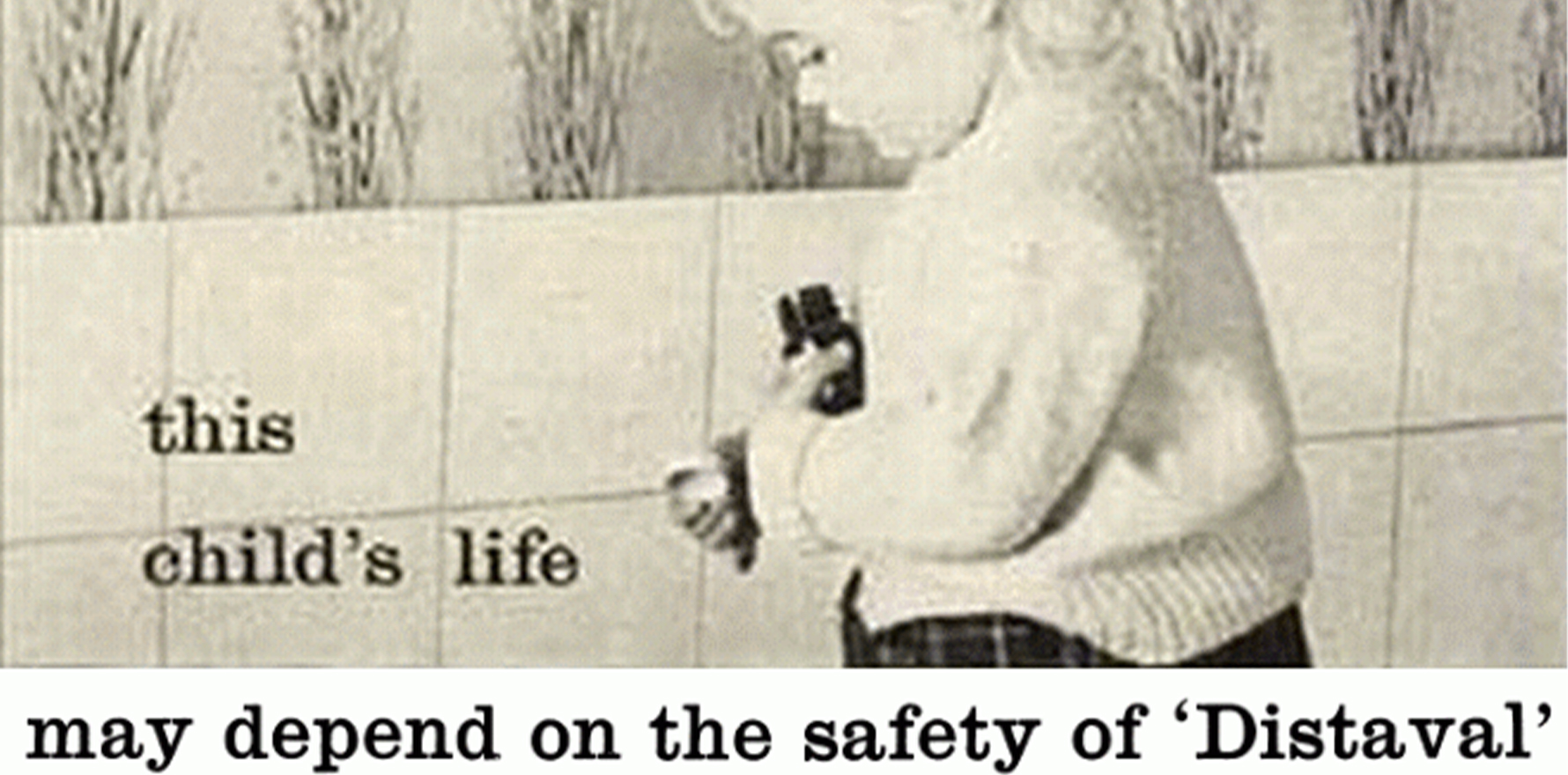

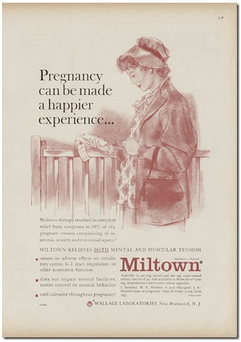

Advertisements from the era reveal that its biggest selling point was its supposed safety.

It was available in Australia under prescription from June 1960 and prescribed to women to ease their morning sickness.

The Australian government banned it on August 9, 1962, but did not immediately block its sale or notify the community of its dangers.

This was already far too late. Officials had been warned nine months earlier by the drug’s distributor, Distillers, that it could be causing congenital disabilities.

“I was a product of that inaction,” Lisa McManus, one of the 125 formally recognised survivors of thalidomide in Australia, tells TMR.

Most of the effects of thalidomide are within her body, invisible to passers-by.

“If you look at me physically, you’d think I’ve got short arms,” she says.

“To look at me, there doesn’t seem to be other issues.”

But the Bendigo mother of two is blind in one eye and suffers from diabetes and severe vascular disease. She also has kidney issues, peripheral nerve damage and feels constant pain that is worsening as she ages.

Other survivors are missing or have shortened arms and legs, are hearing or vision-impaired, have internal injuries, heart or spinal problems or malformed genitals.

“I was a kid with short arms but feisty, rode horses and pushbikes, learnt to drive cars and did ballet dancing,” Ms McManus adds.

“But it’s these last few years that things are slowing down.”

Still, that feisty spirit from her youth remains as she’s picked a fight with the federal government to compensate the individuals affected and apologise to a cohort of loving but forgotten parents.

“We just kept looking, and the further we looked, the guiltier the government became, and it’s a stinking, stinking, stinking pie, and the government had a dirty finger in it,” she said.

She rallied other survivors, encouraging them to push for funding that would help them to modify their homes and pay for growing medical bills as their bodies rapidly age.

“I don’t care if you take a crayon and hold it between your teeth and write something, it’s still powerful,” Ms McManus says.

Life-changing impact

About 40 per cent of the children born with defects caused by thalidomide died in their first year of life.

In late 1961, Sydney obstetrician Dr William McBride concluded thalidomide was causing congenital disabilities in newborns and alerted the medical community with a letter in The Lancet.

Just last month, the Australian government offered survivors compensation for the first time.

It has set aside funds for a one-off tax and income exempt payment in 2020-21 and ongoing payments each year from 2021-22.

Payments will be scaled according to the level of disability, and two separate funds will help survivors with healthcare costs and daily living expenses, plus support to apply for those funds.

It’s a small win for a group of individuals living with the consequences of thalidomide.

For Ms McManus, who was mentioned by name by Health Minister Greg Hunt on budget night, it’s the culmination of six years of non-stop advocacy.

“For four years I’ve been battling with this man – we’ve danced together, the minister and I,” she says.

Trying to explain to parliamentarians the gravity of health outcomes stemming from thalidomide hasn’t exactly been smooth sailing.

“I said to (Minister Hunt) you’re not getting how ragged our bodies are, and what a huge decline [we’re experiencing now],” Ms McManus says.

“We’re noticing weekly things we could do one week that we can’t do the next.

“And he seemed to listen.”

Women have faced particular challenges.

Some have had early hysterectomies or endometrial ablations to try to stop menstruation, while others have never had a period.

“One lady has to sit on the floor and wiggle backwards, so her underpants come down, and you can’t do that in a public toilet,” Ms McManus said.

Another woman likes to wear skirts, but because of significant arm impairments, she couldn’t pull her underwear on or off, or in her younger years, change pads or tampons. She instead would sit on a towel at home for the duration of her period, relying on a carer to change and reposition her.

For a woman without arms or legs, breasts can be one of the few markers of womanhood and sexual identity, but even they have proven to be a challenge.

Some women have elected to have their breasts removed in double mastectomies, or significantly reduced with breast augmentation to prevent injury caused by becoming unbalanced and falling or getting burnt on hot plates.

“They were the only healthy things on their bodies, and yet thalidomide was saying ‘We’ve got to get rid of them, they’re in the way,” Ms McManus says.

A push for acceptance

At least 10,000 babies across the globe were born with defects, but the way the drug shaped their bodies and lives differs from person to person.

Some have never held hands with another person, or been in relationships, while others have fallen in love, started families, studied, travelled and worked.

But many Australian survivors have also struggled with their identity in the face of bullying as children and adults.

Survivor Trish Jackson, 58, has spent years working to change people’s attitudes towards others who look different.

Until recently, she shared her experience with 12,000 students across 50 schools each year by getting them to draw with pencils held between their toes and giving motivational speeches about acceptance.

“Usually when I go out, people laugh at me, they stare at me and whatever,” the mother of one told TMR from her home in Morayfield, north of Brisbane.

“But when you’re on a stage looking down at 75, 100, 200 kids just looking at you with wide eyes and amazement, it’s the best feeling.”

Her influence on children is evident.

One afternoon, Trish’s husband Trevor was posting some mail when he was approached by a woman who asked if it was his wife who had spoken at a nearby school a week earlier.

“She said ‘My son is autistic and he hardly speaks, and it’s a half an hour drive from the school back to home, and usually I get a ‘hello’ and I’ll ask how was school and get one-word answers,” Ms Jackson recalled.

“But the day I spoke at the school she said he didn’t stop talking for the half-hour drive home, and he’s never spoken like that.

“It just blows me away.”

One day, after a speech, Ms Jackson was approached by a little boy, who uncurled a closed fist to reveal three marbles in his hand. Offering them to her, Ms Jackson turned him down, but he insisted she take them.

“He said ‘I want you to have them because if you have them, you might remember me, because I’m never going to forget you’. Those marbles sit on my desk, and I look at them every day,” she said.

It’s been quite the journey for a girl who was rejected by every school her mother approached in Brisbane, bar one.

“She’s my everything,” Ms Jackson says of her mother, Margaret Smith.

“There was no such thing as teacher aides or personal assistance for disabled kids back in those days.

“Mum worked at another school, and in her lunch hour, she would drive to my school, take me to the toilet and then drive back to her school.

“She did that every day I was at school from grade 3 to grade 12.

“It was amazing what she did.”

Ms Jackson said her mother was given thalidomide by a Townsville doctor to treat a migraine.

“She later she realised she was pregnant, and when the news broke about thalidomide she went back to her doctor to say ‘What do I do?’ and he had destroyed all her medical records, all of the family’s records, everything,” Ms Jackson said.

“He denied that she was ever a patient of his.”

During hearings for a Senate inquiry into support for Australia’s thalidomide survivors, individuals told of the ways their lives had been affected by thalidomide embryopathy.

They spoke of complex and chronic health conditions, mental illness, poor social and emotional wellbeing, diminished opportunity and the financial costs of their disability.

“Despite these effects, thalidomide survivors are still fighting to retain their independence, their dignity and to have their voices heard,” an interim report presented by the Senate committee states.

“The families of thalidomide survivors, particularly survivors’ parents, spouses and children, live with the effects of what thalidomide did to the person they love.

“Evidence before the committee conveys the trauma, guilt, and life-changing carer responsibilities experienced by survivors’ parents.

“The spouses and children of survivors have missed life opportunities and continue to make considerable personal commitments as they provide care and support to their loved one.”

Overwhelming guilt

Mrs Smith rarely talks about thalidomide. Like many mothers who had no way of knowing its effects, she harbours terrible guilt.

One afternoon while Ms Jackson was visiting her mum, who is now in aged care, a nurse remarked on the difficulty in getting her to take thyroid medication.

“Mum just turned around, pointed at me and said ‘Well look what happened last time I took a tablet’,” she says.

“That’s the only time mum’s ever spoken or done anything like that to me, and it was a huge slap in my face, but that’s the guilt she carries.

“It broke my heart. I just went home and cried afterwards.”

Jordan Steele-John is the youngest senator in Australia, and the first with a lived experience of disability.

The battle for compensation by 35 thalidomide survivors who weren’t part of a 2014 class action was one of the first things he looked into when he became a member of parliament for the Greens last year.

Survivors who were part of that class action received lump sum compensation payments, while a smaller group who weren’t, due to waivers their parents signed when they were younger, have been receiving annual payments from the company that bought the distributor of thalidomide in Australia.

They’d been knocking on the doors of politicians across the political spectrum for years, trying to get someone to listen.

“You’re standing up against the fact that our political system has only been designed to care about large groups of people with a lot of money, and this is a small group of people with no money,” Senator Steele-John tells TMR.

“Nobody could be bothered to listen to Lisa, to Trish, to any of the survivors, and actually take action.

“There was a big misunderstanding, an unwillingness to engage with what thalidomide was and the case for compensation and recognition, so they kept getting stuck in a loop of hearing ‘Have you heard about the NDIS?’ That’s not the point.”

The senator said his parliamentary colleagues had also shown a reluctance to engage with a group of individuals who were less polished than the corporate lobbyists who typically move through the hallways of Parliament House.

“So many politicians have forgotten that their job is to work for the people that elected them, rather than the people who give the most money or the people that are key to their faction or career advancement,” Senator Steele-John says.

He has been told by Health Department officials that funds allocated in last month’s federal budget won’t carry an individual cap, but remains sceptical.

“I will believe that next year when they publish the rules around access, and they’re not restrictive, because it would be the first Australian government program ever created that doesn’t have the assumption the recipient is trying to rip it off,” he says.

He notes the annual payments aren’t indexed, which means their overall value will decline over time.

Learning of the government’s announcement stirred up a tangle of emotions in Ms Jackson.

“It was justification that we were right, that the government did stuff up and they should help us,” she says.

“All that fight, the headaches, the cost. We did it on our own, without lawyers, without anyone – a disabled group that fought the government and won.

“That was huge.

“But then you read through it and think, is this real? What are going to be the loopholes in there so they cannot give us as much? That’s when the anxiety set in.”

And so, the handful of people who survived one of the worst medical disasters in history continue to wait and see the results of a battle they should never have had to fight.

“The government promised big stuff, but will they deliver?” Ms Jackson wonders.