The association between rheumatological disease and cancer all comes down to tolerance, according to one expert.

Rheumatoid arthritis patients are less likely to develop certain types of cancer, but more likely to die from them, new Australian data shows.

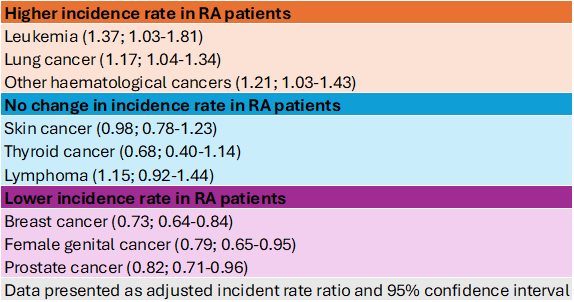

Early research has hinted that patients with RA have an increased risks of particular types of cancer compared to disease-free individuals, which was thought to be due to the underlying pathophysiology of RA rather than treatment with DMARDs.

Now, new research has teased out the link, showing RA patients have a lower overall incidence of cancer – but have higher post-cancer mortality rates compared to people without RA.

Using data from the Western Australian Rheumatic Disease Epidemiological Registry, researchers compared the cancer rates of 13,000 patients with RA to 30,000 controls over 30 years.

They found that while fewer RA patients developed cancer (17% versus 25%), they were more likely to die during the follow up (16 versus 11 in 100 person years) and die sooner (39 months versus 63 months).

Patients with RA were 33% more likely to die from any cancer after being diagnosed with any cancer compared to the control group, 50% more likely to die after being diagnosed with skin cancer and 57% more likely to die after being diagnosed with breast cancer.

“Cancer and autoimmune disease like rheumatoid arthritis are basically two sides of the same coin – it all has to do with tolerance,” said Emeritus Professor Johannes Nossent, Winthrop Professor of Rheumatology at the University of Western Australia and the study’s lead author.

“In rheumatoid arthritis, the body has become intolerant to a certain antigen and starts fighting it off with inflammatory processes. But in cancer, the body is normally intolerant towards foreign antigens, then it suddenly becomes tolerant and allows the cancer cells to grow,” the consultant rheumatologist and clinical academic at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital continued.

“The mechanisms and the cells are basically the same – they’re just being steered in different directions.”

The researchers noted that while the potential drug-induced carcinogenic effects of methotrexate and tumour necrosis factors had been refuted, other medications could still affect the cancer risk in RA patients.

“The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) has been shown to reduce cell migration and increase sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs, and this mechanism has been postulated as an explanation for the reduced cancer incidence rate in RA.

“With near-universal use of NSAIDS and low-dose methotrexate as the anchor drug for RA, this could explain the reduced risk for breast, genital and gastrointestinal cancer, although other contributing factors (e.g., metabolic syndrome, family history) cannot be excluded,” the researchers wrote in the conclusion of the manuscript.

Related

But the researchers did suggest that the multimorbidity of having both RA and cancer exerted a significant influence on cancer survival in patients with RA.

“This ongoing fight between maintaining tolerance and not becoming intolerant to foreign antigens is a basic conundrum of the discussion between rheumatology and cancer,” Professor Nossent explained.

“That is why we’ve done a number of studies in other rheumatic diseases – including lupus and inflammatory myopathies – which show the same thing; an increased risk for a certain number of cancers, but they vary slightly by disease,” he told Rheumatology Republic.