Research hints that acute inflammatory responses are actually protective effect against developing chronic pain.

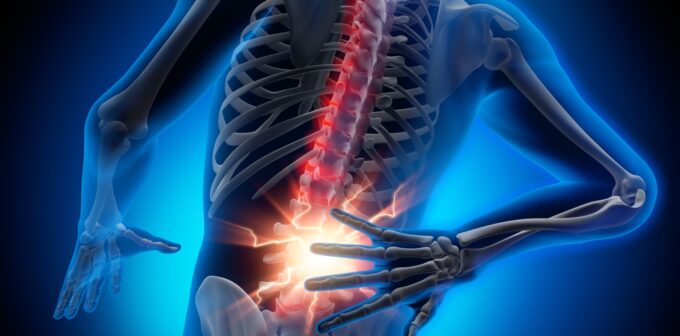

Using anti-inflammatories like ibuprofen for back pain could delay recovery and even lead to chronic pain, new research suggests.

And allowing acute inflammatory responses to occur, without trying to treat them with medication, could actually have a protective effect against the development of chronic pain, according to a study of patients with low back pain.

Melbourne pain specialist, Associate Professor Michael Vagg, who described the claim as “eye-opening”, said that while more research was needed, the findings had the potential to change practice.

“There has been a huge amount of work in recent years looking at the interactions between the immune system and the development of chronic pain,” he said.

“The things which underly the transition from acute to chronic pain have really been hard to pin down but it really adds a lot of weight to the idea that the dysregulation of the immune system contributes significantly to the development of chronic pain. The implication [is] that using anti-inflammatory medications like steroids and NSAIDs early on is, frankly, a little frightening.”

The research, published in Science Translational Medicine, examined the blood cells of 98 people with low back pain over three months and compared the inflammatory changes of those whose pain resolved with those who were in persistent pain.

It appeared the short-lived inflammation in the body lowered the chances of that initial pain becoming chronic pain.

Because mouse studies suggested that treatment with steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prolonged pain, the researchers decided to also examine the relationship between analgesic drug usage and back pain in a large human study from the UK Biobank project.

They found people with acute back pain who took NSAIDs were almost twice as likely to have chronic back pain after three months, but that these links were not found with other analgesic medication categories.

“Thus, despite analgesic efficacy at early time points, the management of acute inflammation may be counterproductive for long-term outcomes of lower back pain sufferers,” the researchers wrote.

Professor Vagg said the findings could spark “a very significant rethink about how we manage acute pain, in particularly back pain”.

“We’ve been telling people not to use or to use a minimal amount of opioids, not to use benzodiazepines, and not to bother using paracetamol because it doesn’t work,” he said.

“Anti-inflammatories have almost been the only ones that people have not accused of being a problem. And now it may actually be the case that without realising it, that we may have been, at least in some patients, potentially facilitating the development of the transition to chronic pain.”

Professor Vagg said this had been suspected before with opioids, with German studies about 15 years ago suggesting long-term opioids could suppress the immune system and facilitate chronic pain.

“But as far as I’m aware, we’ve never accused the anti-inflammatories of doing that. This is quite an eye-opening claim,” he said.

Professor Vagg said clinicians did not need to panic about the findings until more research confirmed the link, but should be mindful when prescribing anti-inflammatories for back pain.

“If you give someone anti-inflammatories or indeed any other medications in an acute back pain setting, give them two or three doses for it to help and if it’s not helping take them off, because what this suggests is that the real long-term implications for practice are not clear,” he said.